Article 7 (Registration, name, nationality, care): All children have the right to a legally registered name, recognised by the government. Children have the right to a nationality (to belong to a country). Children also have a right to know and, as far as possible, to be cared for by their parents.

Article 8 (Preservation of identity): Children have the right to an identity – an official record of who they are. Governments should recognise their right to a name, a nationality and family ties.

How easy it is to take these rights for granted. Most children, whether living with their birth parents, other relatives, in foster or adoptive families, or even in an informal care situation, enjoy these rights. Their identity and the right to belong to their community and country is secure. But what about children who, because of intolerable conflict situations in their country of birth, are removed to another, safe country, perhaps on another continent? War has firstly violated their right to be cared for by their own parents, but they retain their identity as a citizen of that country, right?

A report by The Independent has the headline: ‘Hundreds of Afghans who grew up in UK face deportation to a country they “barely remember”.’ This refers to children who were sent to the UK to live with British foster parents; they went to school here, took GCSEs and A Levels and became active members of their communities. Sadly, they mostly had little or no contact with their country of birth. But as these young people reach the age of 18 they face deportation ‘to a country that they barely now remember’. Under international law, the UK can’t send unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors back to their home country, instead it issues temporary leave to remain, which ends of course, on reaching adulthood. It then becomes much harder for them to apply for permanent asylum in their adopted country.

What awaits them when they return to Afghanistan? Often, they can’t trace their birth families, not having had contact whilst living in the UK. The article says: ‘Their Westernised mannerisms and accents also mean they are often regarded with suspicion…..and some…..have been left homeless, chased by the Taliban, kidnapped, ransomed and beaten.’ Those who remain in the UK, waiting for their application to be considered, are in limbo. They can’t get a job, they can’t go to university. The article doesn’t say whether they can remain living with their foster families, but in any case, this isn’t their country any more. So, while these young adults have a registered name and they have ties to a ‘temporary’ family, they don’t ‘belong to a country’, surely a huge part of anyone’s identity. Needless to say, both the UNHCR and the UK’s Children’s Commissioner’s office have criticised The Home Office’s policy towards asylum-seeking children. You can read the full article here.

Yet another example of the trauma, devastation, even the ruination of young people’s lives caused by war.

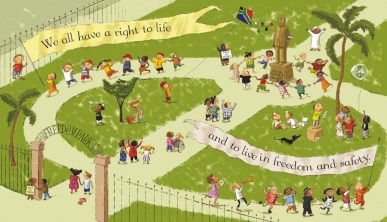

‘We all have the right to belong to a country’

We are all born free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures

Published by Frances Lincoln Children’s Books www.franceslincoln.com in association with Amnesty International.

A