I don’t know if you’ve noticed the English Heritage Blue Plaques on buildings in London (and elsewhere), commemorating someone’s life or work at that place. I’m going to look at four I’ve found, you will have heard of one of these people, the others probably won’t be familiar, but they were all Christians who changed many peoples’ lives for the better, and hopefully changed the opinions of the politicians and authorities of their day. You might notice that all these people had very posh addresses, but in the 17 and 1800s anyone who had any influence usually had family wealth which enabled them to pursue their Christian/socialist ideals. Admirable, considering many wealthy people just spent their lives in idle luxury, not caring about the plight of those around them or elsewhere in the world.

So, in alphabetical order:

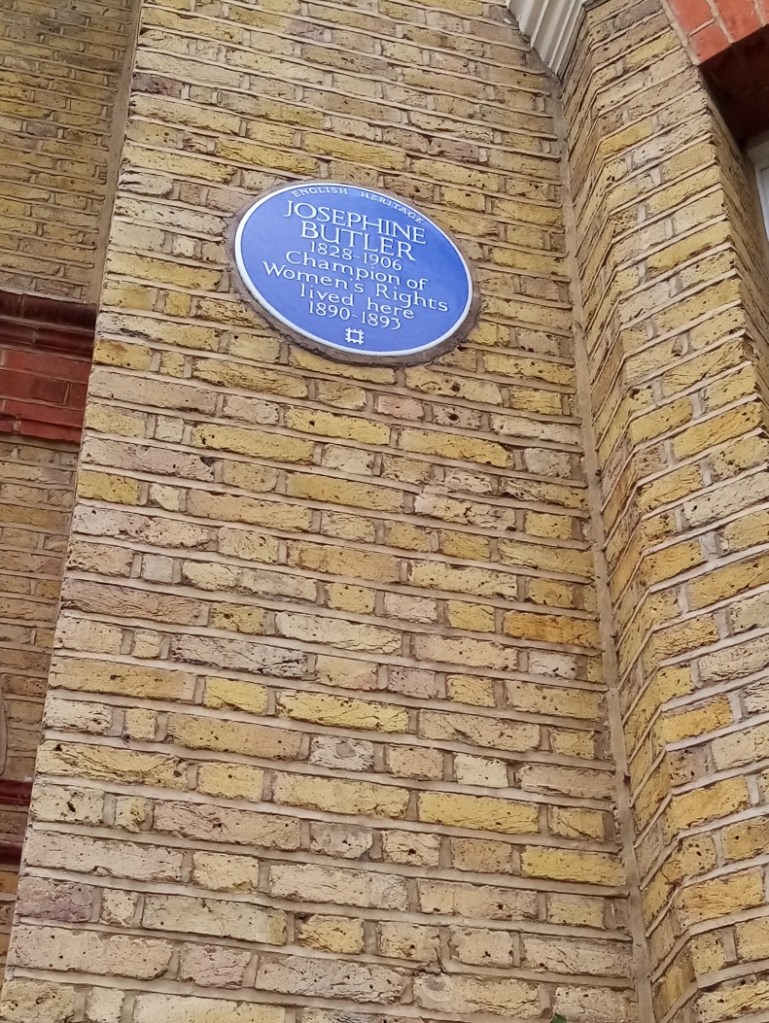

Josephine Butler (1828 – 1906) is described on her Blue Plaque in Wimbledon as a ‘Champion of Women’s Rights’ but she was much more than this. She was a devout Christian and at the same time, a passionate feminist, two things that did not go together in Victorian times! Brought up to a sheltered, privileged lifestyle, she turned her back on a life free from cares and responsibilities to bring the hidden underworld of the Victorian sex trade into the light. She was appalled that teenage girls and young women were kidnapped and sold to brothels, and questioned the double standards of the time, that men seeking sex from prostitutes were ‘sowing wild oats’ or ‘gaining experience’, but the young women they paid for were considered unclean, immoral and denigrated to the lowest station in life. The concept of consent didn’t exist; females were bought and sold as chattels. Josephine helped hundreds of girls and women escape prostitution, being instrumental in the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which addressed sexual offences against women and minors and fixed the age of consent to 16 years old. Despite her pioneering work for women, Josephine Butler has been criticised by secular feminists for being too ‘Christian’, but for Christian historians she’s too feminist! I think it’s more important to remember her momentous achievements rather than how she’s identified by others. Premier Christianity Magazine comments: ‘she was the most distinguished woman of the 19th Century, but she has vanished from the pages of history.’ Well, now you know!

Josephine Butler’s posh address off Wimbledon Common

Portrait by George Richmond 1809-1896

Wikimedia Commons File: Josephine Butler.jpg

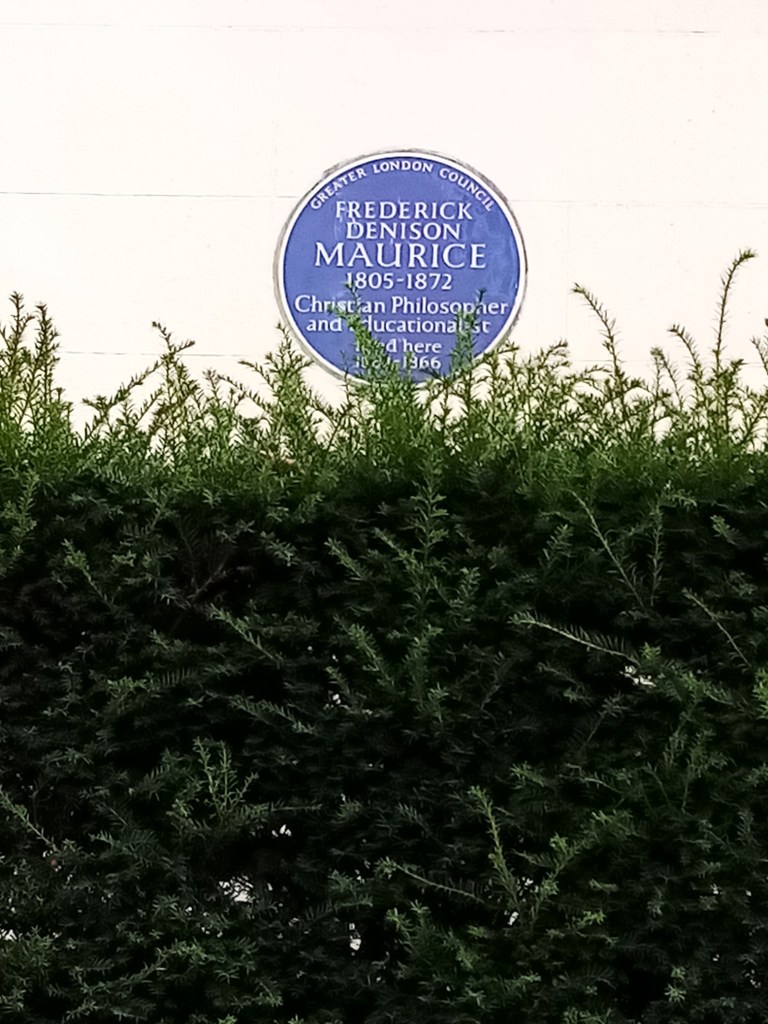

Frederick Denison Maurice (1805 – 1872) His plaque says ‘Christian Philosopher and Educationalist’ and he was prominent in Christian Socialism. He was an Anglican priest, ordained in 1835, and in 1838 he wrote ‘The Kingdom of Christ’, a book about how God’s Kingdom should be here on Earth now, not a Heaven that we go to when we die. A Rob Bell (‘Love Wins’) of his day! Living in London, he said ‘the condition of the poor pressed upon me with consuming force’. Working class men trusted him when they distrusted other clergymen and the church, because of his social action approach. He believed that ‘Christianity rather than secular doctrines were the only sound foundation for social reconstruction.’ From 1848 to 1854, FD was Leader of the Christian Socialists, and he was characterised as their spiritual leader because he was interested in theological aspects rather than just social action. In other words, he wanted to put the Words of Jesus into action. I would have loved to have met him and discussed his work!

FD’s posh address just off Regent’s Park. Nice!

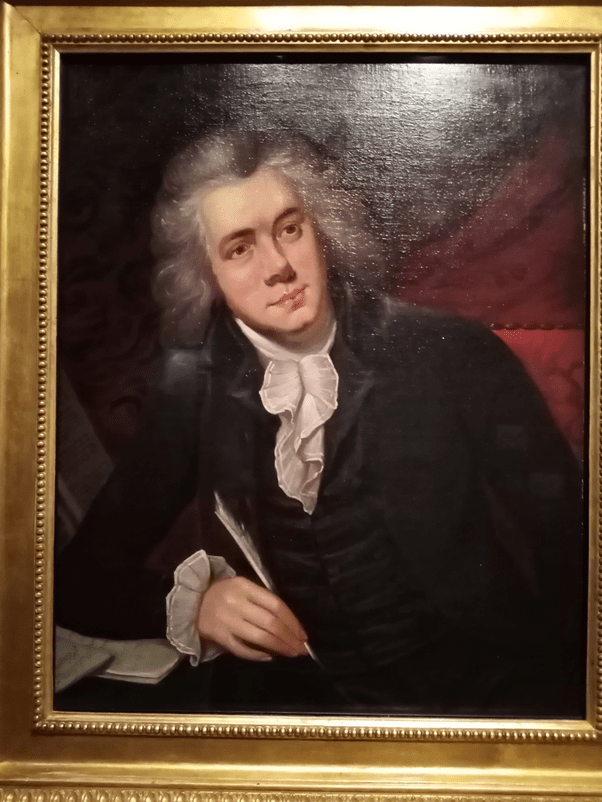

William Smith (1756 – 1835) His plaque says ‘Pioneer of Religious Freedom’, Wiki says ‘William Smith (abolitionist.)’ So which was he? The answer is both: he was an English Dissenter; they were Protestant Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 17th and 18th Centuries because they disagreed with state intervention in religious matters. William was instrumental in bringing political rights to dissenters, imagine not being able to vote because of your religion, that’s so wrong! He was also a friend of William Wilberforce (more of him later) and a member of the Evangelical group, the Clapham Sect, with Wilberforce. This was a multi-denominational group of church leaders and influential, prominent individuals who saw the slave trade as immoral and were in a position to be able to do something about it. The two Williams joined with other Christians of different denominations to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the Americas. Smith was also at the forefront of campaigns for social justice and prison reform, and he also co-founded the London Society for the Abolition of Slavery in our Colonies. Ending the transatlantic slavery trade was just the beginning, the fight would continue to free the slaves in the Southern States of America and the West Indies. Interesting fact: William Smith was the grandfather of Florence Nightingale. She turned out to be considerably more famous than him!

William shares his posh address in Queen Anne’s Gate, St James Park, with Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Fisher.

Portrait by Henry Thompson, English Portrait painter 1773-1845

Wikimedia Commons File: William Smith Thompson.jpg

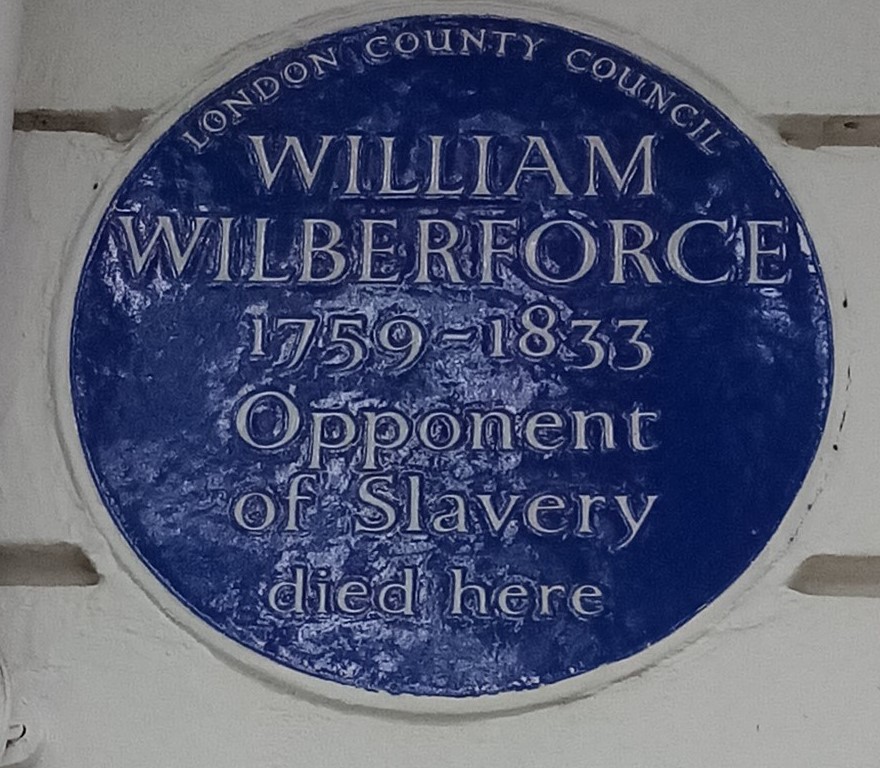

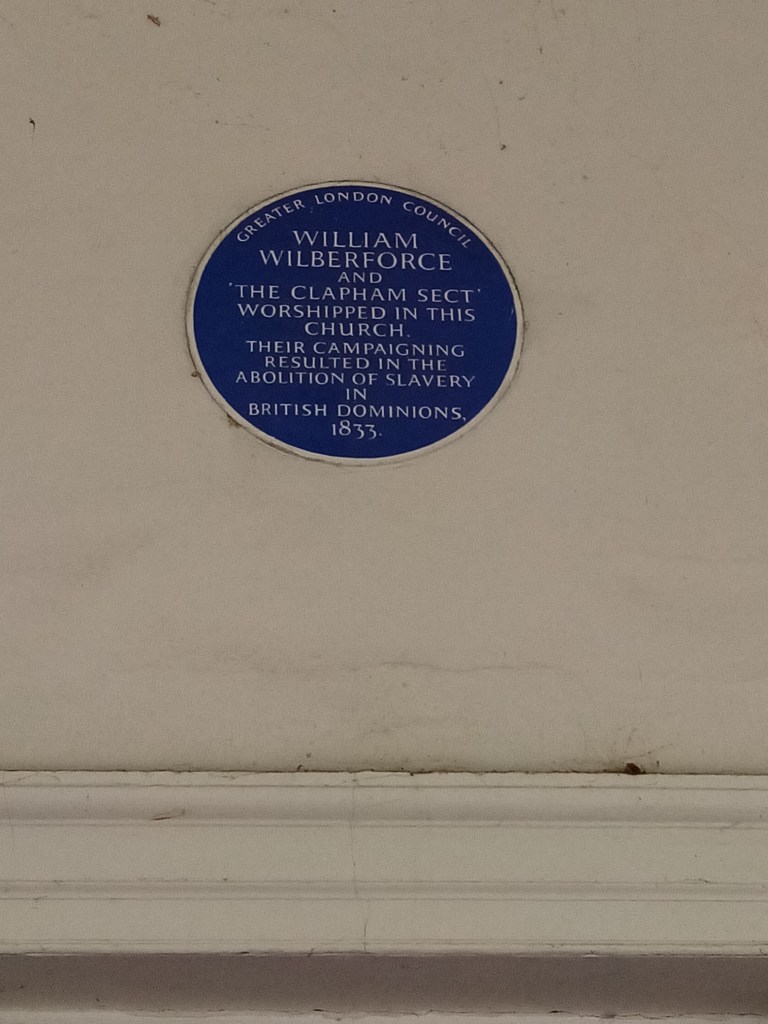

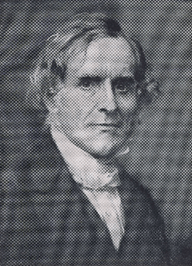

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833) entered politics as an Independent candidate in 1784 and following a dramatic Christian conversion in 1785, decided to dedicate the rest of his life to the service of God. He initially thought of leaving politics and taking up church ministry but was counselled by friends John Newton and William Pitt (the future Prime Minister) to remain, arguing that he could have more influence as an MP. They got that right! Wilberforce became involved in the Abolition of the Slave Trade following a meeting with some influential activists who were horrified by the cruel treatment of African slaves by colonial plantation owners in America and the West Indies. They encouraged him to bring the case for abolition to Parliament, but Wilberforce felt he was ‘unequal to the task allotted to him,’ there being massive opposition from slave owners and British businessmen. As we’ve lately become more aware, so much of Britain’s wealth was built on the slave trade, and many people in the 17 and 1800s had a vested interest in continuing the slavery industry. Wilberforce gets all the credit, but it’s important to remember that a diverse group of hundreds of people were involved in the movement: Quakers, Anglicans, Evangelicals, like minded businessmen, titled men and women, and former slaves – and even former slave owners! Wilberforce’s poor health forced him to hand over the leadership of the campaign to the even more radical Thomas Fowell Buxton in 1825. On 26th July 1833 Wilberforce heard that passing of the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery was guaranteed; he died three days later. The actual Act was passed into law one month later in August 1833. At least he lived long enough to know!

Posh address: Cadogan Place, Chelsea, and Plaque at Holy Trinity, Clapham

Portrait of Wilberforce in the Museum of London Docklands, and Holy Trinity Clapham