I first thought of exploring the connection between churches and the military after visiting the Royal Military Chapel (or Guards Chapel) on Birdcage Walk, just down from Buckingham Palace. I also read an article in Premier Christianity about the impact of conflict on the Church in Russia and Ukraine; writing about the funeral of Queen Elizabeth ll, the author says: ‘Westminster Abbey was full of soldiers and regimental banners; a spectacular mix of Church, nation and military. But it wasn’t always like this. For centuries after the resurrection of Christ, his followers believed that when Jesus said “love your enemies” he actually meant it. Churches did not allow their members to be soldiers.’* So does the presence of armed soldiers at church services sit well with Jesus’ message to His church of peace, love and unity? Having visited both the Guards Chapel and St Clement Danes, the church of the RAF, I realise that the role of these churches is to support servicemen and women spiritually and in other ways, and to commemorate those who have died in conflicts. All members of the forces: army, navy and air force, are servants of the reigning monarch, formerly Queen Elizabeth ll and now King Charles lll, and many of their duties are ceremonial, as we will see at the King’s coronation on May 6th. Anyway, enough of the philosophising, here are the churches!

Reference: Nick Megoran, A Church at War? Premier Christianity, March 2023

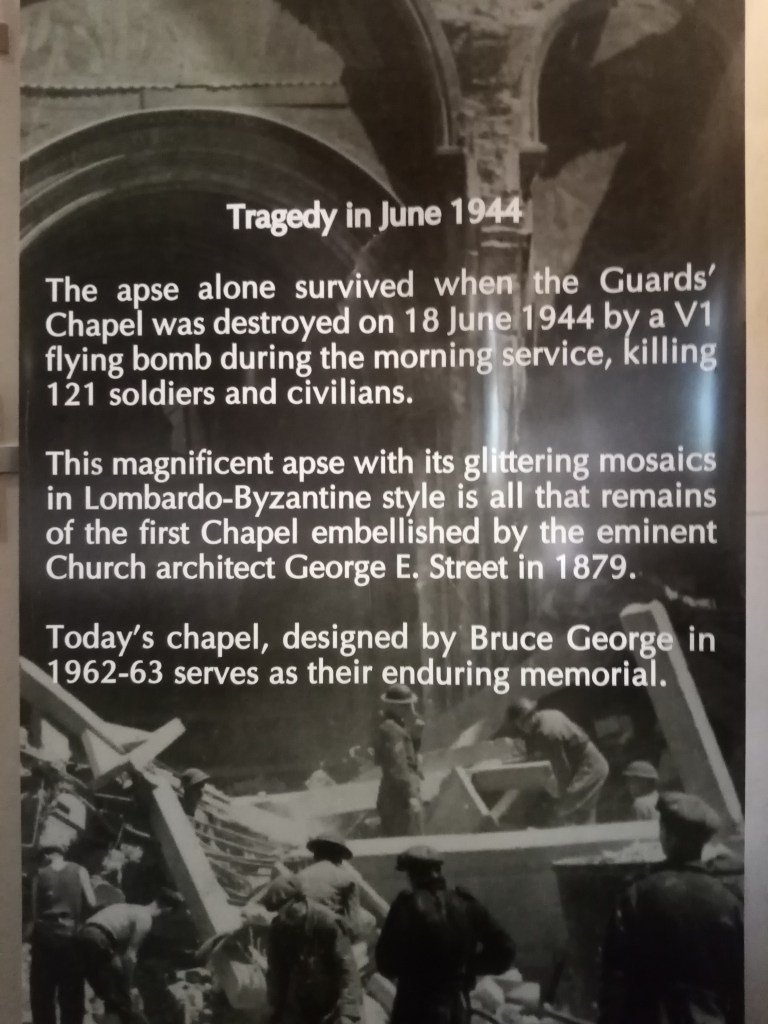

The Guards Chapel

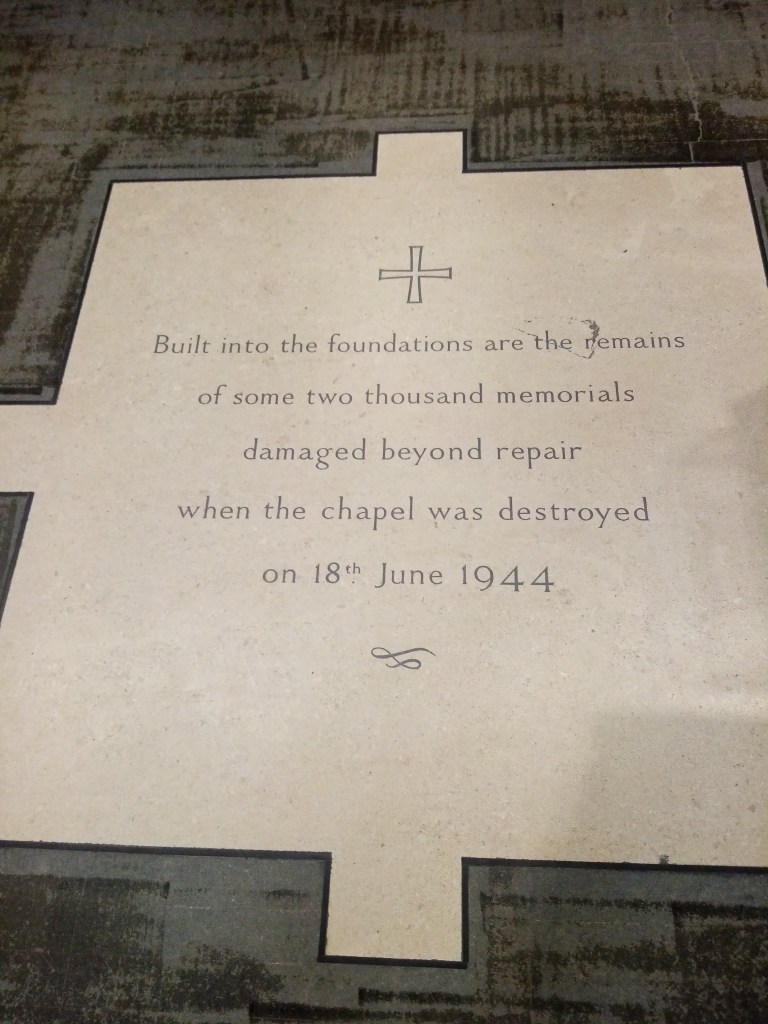

Wellington Barracks, close to Buckingham Palace, was completed in 1834 and its Chaplain, Dr William Dakins, campaigned for a chapel to be provided for the Guards of the Household Cavalry, to enable them to attend church services in their own building. The Royal Military Chapel, St James Park was built to accommodate a congregation of over 1,000 and the first service was held on 6th May 1838. The building was considered rather plain and austere, so money was raised to embellish and decorate the interior and to erect monuments to those who had died in service to their King (or Queen) and country. On Sunday 18th June 1944, tragedy struck when the chapel was hit by a flying bomb which exploded and almost completely destroyed it. 121 people, both soldiers and civilians were killed and many more were injured. The memorials and other artefacts were not reconstructed but all their remains were laid under the floor of the present chapel; ‘the new chapel thus rising from the foundations provided by the old, so forming a physical link between the past, the present and the future’* Amazingly, the apse, font and altar were completely undamaged and have been skilfully incorporated into the new building. The brilliance of the apse and altar are in startling contrast to the plain white walls of the new chapel.

Reference: Major A. G. Douglas, MBE, The Guards Chapel

Font undamaged by the bomb

St Clement Danes, the Church of the RAF

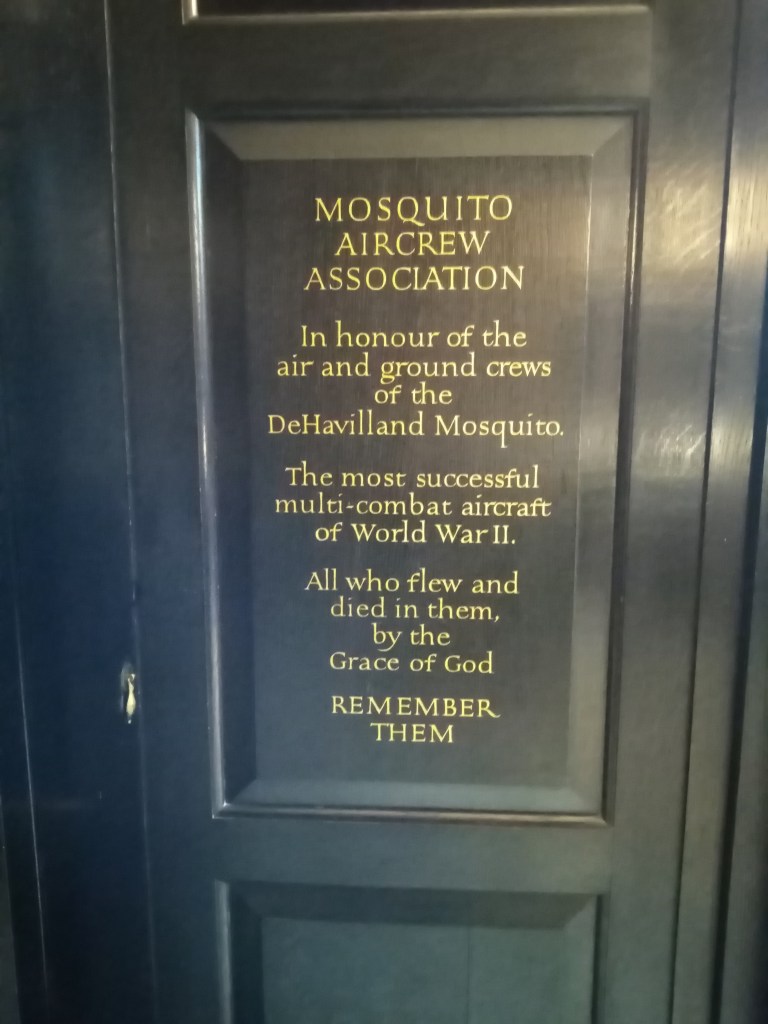

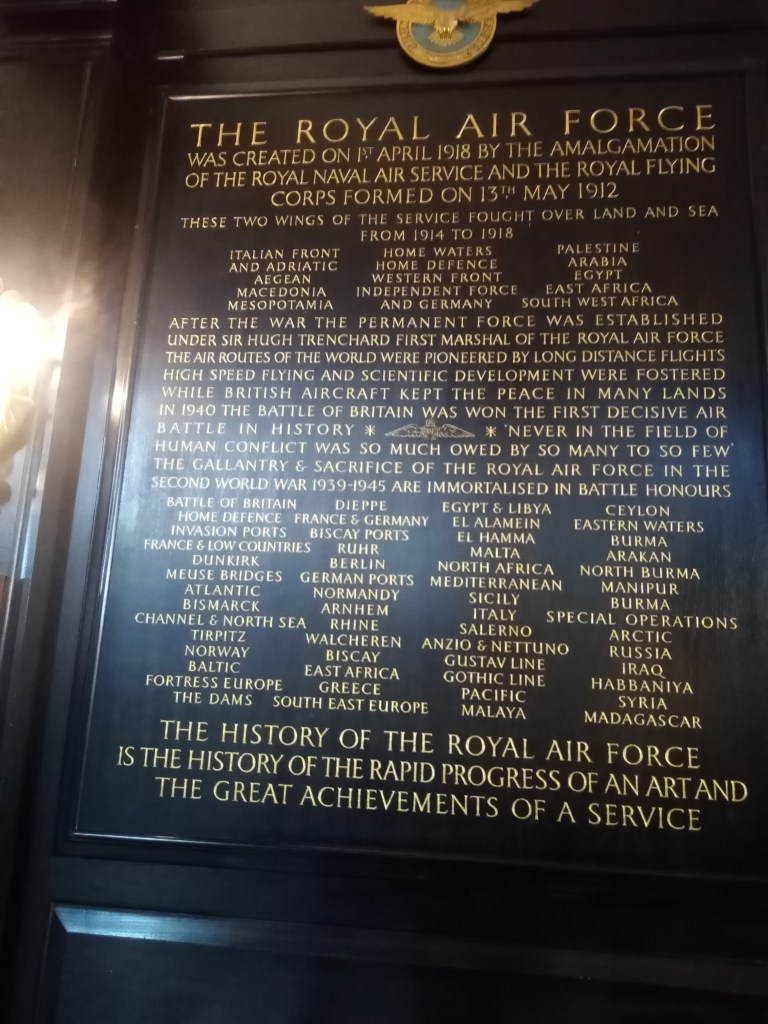

I wrote about this church’s 1,000 year old history two months ago, it’s story continues into modern times. This is another church that received a direct hit in World War ll: on 10th May 1941 an incendiary bomb exploded within the roof space and destroyed all but the tower and some of the outer walls. The night of 10th/11th May was one of the worst of the Blitz, bombing began at 11pm and continued til 5.30 the next morning, but it marked the last major raid of the Blitz. The church was not rebuilt and lay in ruins for over a decade. After the War the Royal Air Force were looking for a central London church to adopt. The Diocese of London agreed that if St Clement Danes could be rebuilt to Sir Christopher Wren’s original design, the RAF could have its central church. An appeal was launched and supported by Air Forces world-wide, and the church was restored and re consecrated as the Central Church of the Royal Air Force in 1958. St Clement Danes states its role ‘is to be a place of regular worship and to be a living memorial to those who died whilst serving in the Royal Air Force.’ The interior of the church incorporates lots of design features and memorials to the RAF which show the skill of those who rebuilt the church from its ruins.

Reference: Leaflets in the church

RAF Floor design

Altar

St Martins in the Fields

Picture from St Martins in the Fields Church website

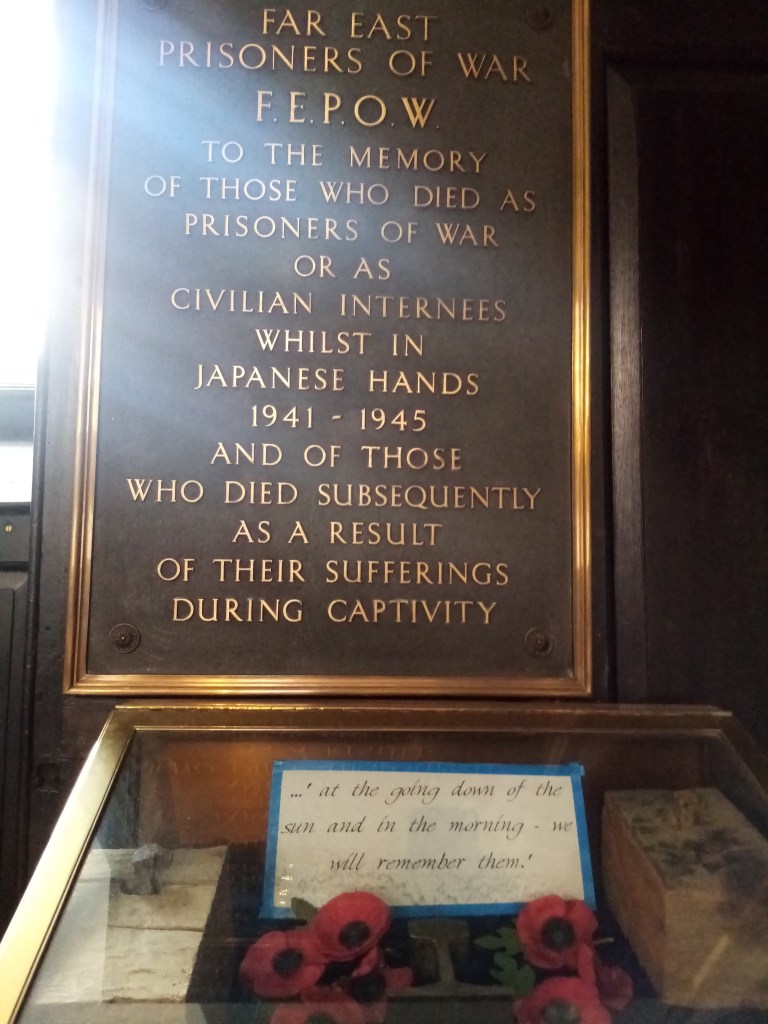

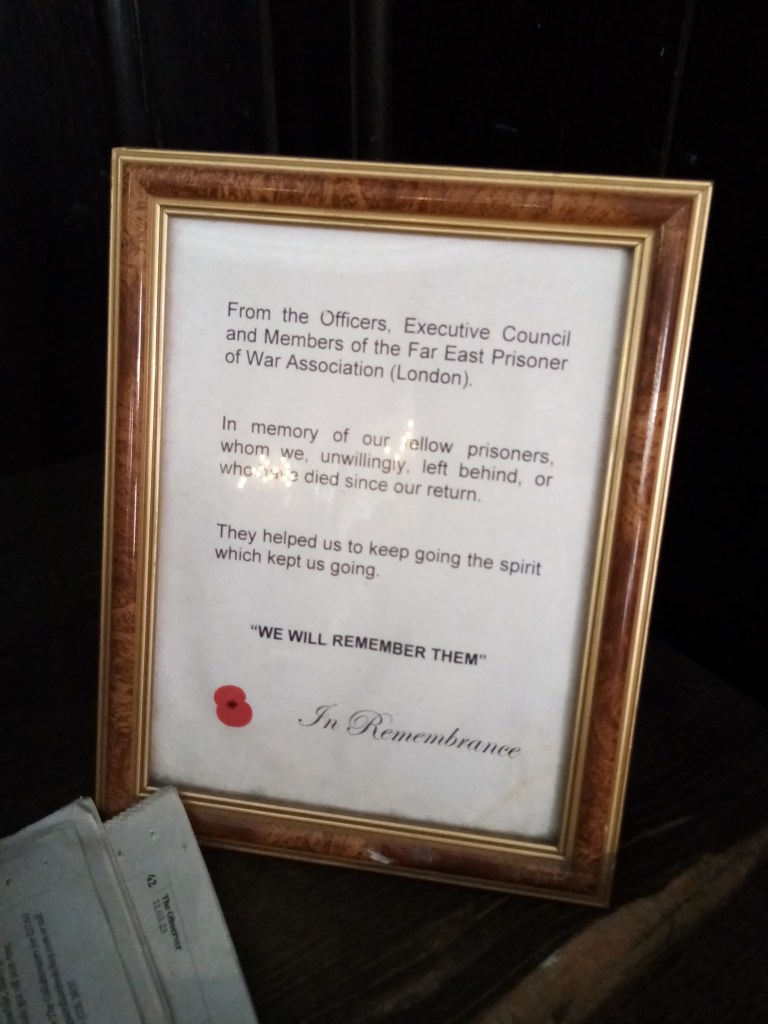

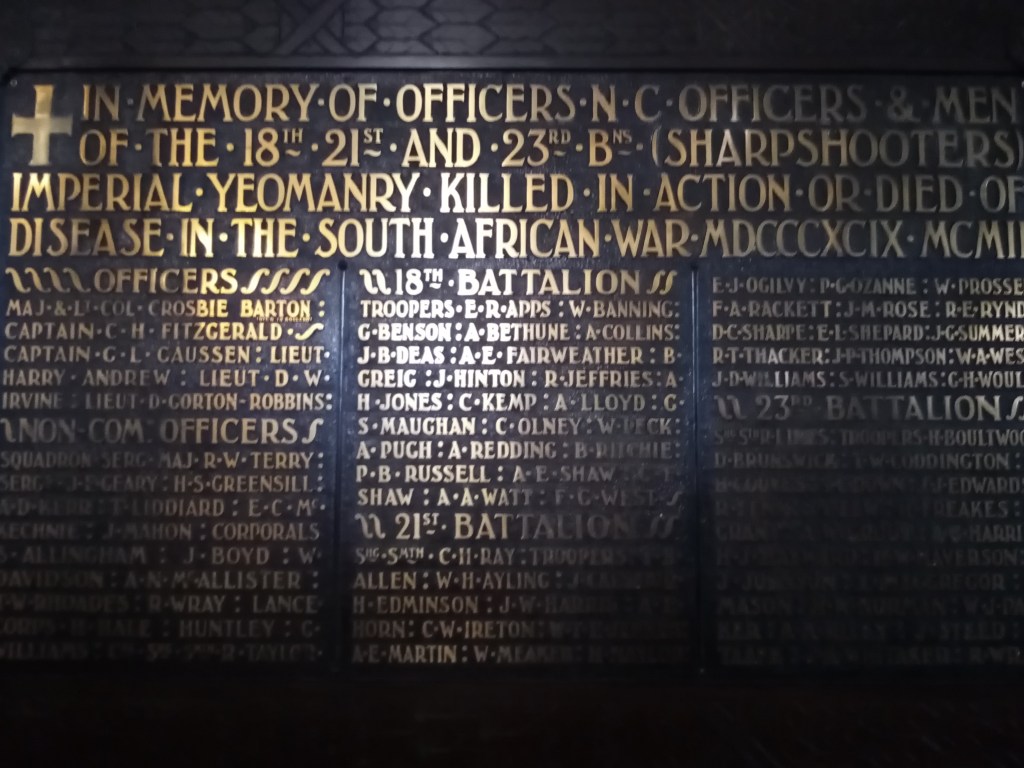

The Vicar of St Martins in the Fields between 1914 and 1926 was Dick Sheppard, who was a member of the Christian Pacifist movement, a theological position which affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. After ordination into the Church of England, Sheppard became a chaplain at a military hospital in France at the start of World War 1, but suffered what today would be diagnosed as PTSD, due to his experiences there and had to return home. This completely changed his view of warfare and he became a life long pacifist. He accepted the living at wealthy, fashionable St Martins, turning the church into a social care centre for those in need, particularly the area’s homeless and this work continues today. Unfortunately Sheppard suffered poor mental and physical health for the rest of his life but continued to campaign for peace, establishing the Peace Pledge Union in 1936 and writing several books about pacifism. He died aged 57 in 1937, two years before the outbreak of World War 2, I wonder if he would have gone on to write about war and peace if he had lived on into the war years? The War Memorials in St Martin in the Fields focus on the suffering that warfare causes, through actual conflict, through captivity, deprivation and disease, and through subsequent post-war health deterioration. This reflects Dick Sheppard’s belief that war is not glorious and good, but causes only suffering and tragedy.

Reference: Wikipedia

St Martin and the Beggar

St Paul’s Cathedral War Memorials

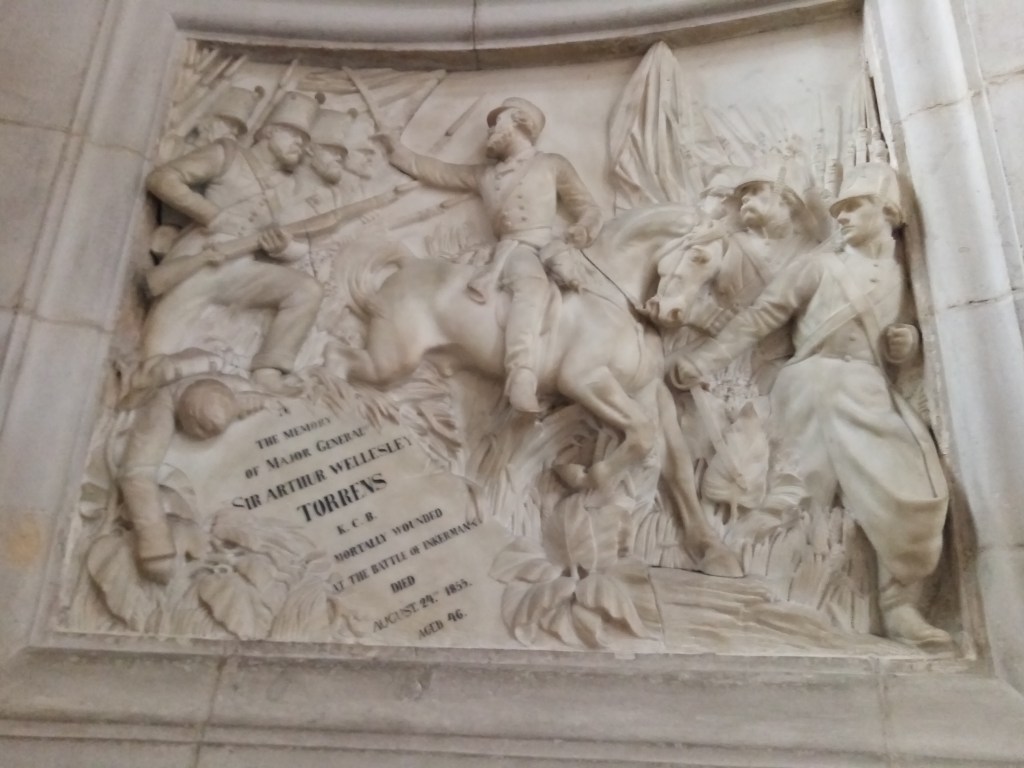

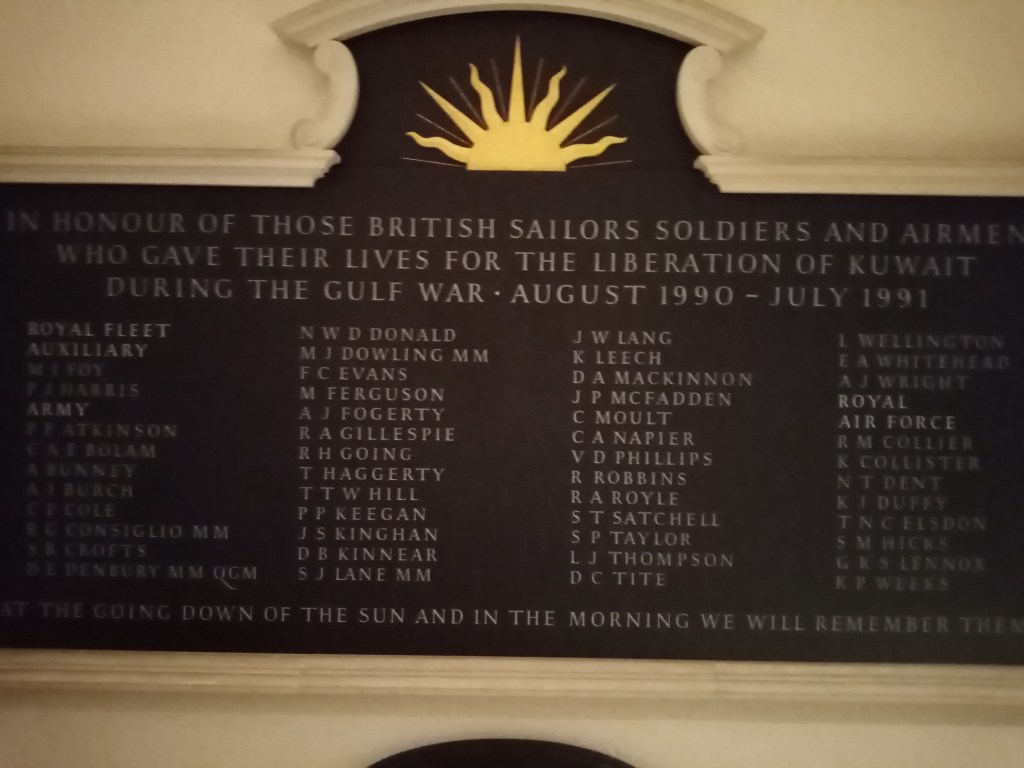

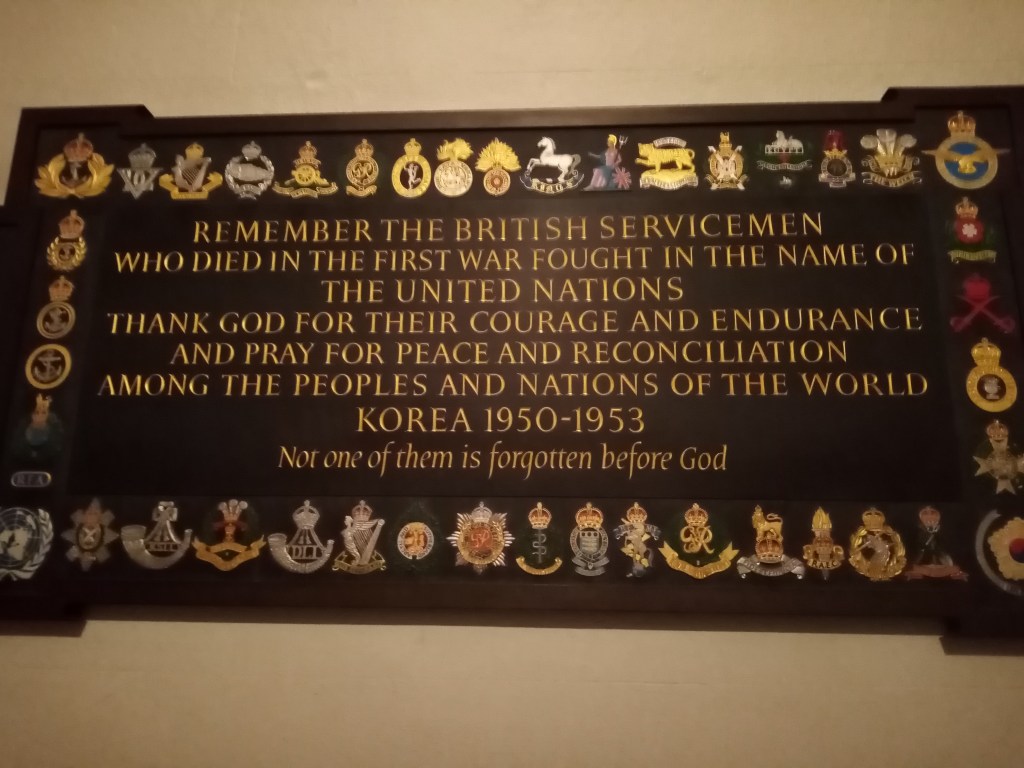

I’m finishing this month with photos of some of the War Memorials in St Paul’s. Some of these are very elaborate and detailed and seem to glorify war, or at least revel in victory. The photo above shows a couple from Greek mythology perhaps, standing beside a weapon of war, a cannon. Some mixed messaging, I think! It’s interesting how the casualties of war are commemorated and remembered: how the words and images used on the memorials have changed over time so that the later ones are less triumphant in victory, and more respectful and thankful for the sacrifice made by brave service men and women for their country.

Monument to the 1st Duke of Wellington

Baby wearing a battle helmet!