This month I visited a few more chapels in and around the City. The difference between a church and a chapel is that churches have a permanent congregation with a minister to conduct regular services, whereas chapels are usually smaller places of worship and don’t have regular services (although some do, as I found out.) There are chapels in the grounds of hospitals, schools, private residences, and these days, in airports and workplaces. However, the four I explored are in none of these places! One is in a former monastery, one is part of the Inns of Court, and two are part of larger churches.

Chapel of the Charterhouse

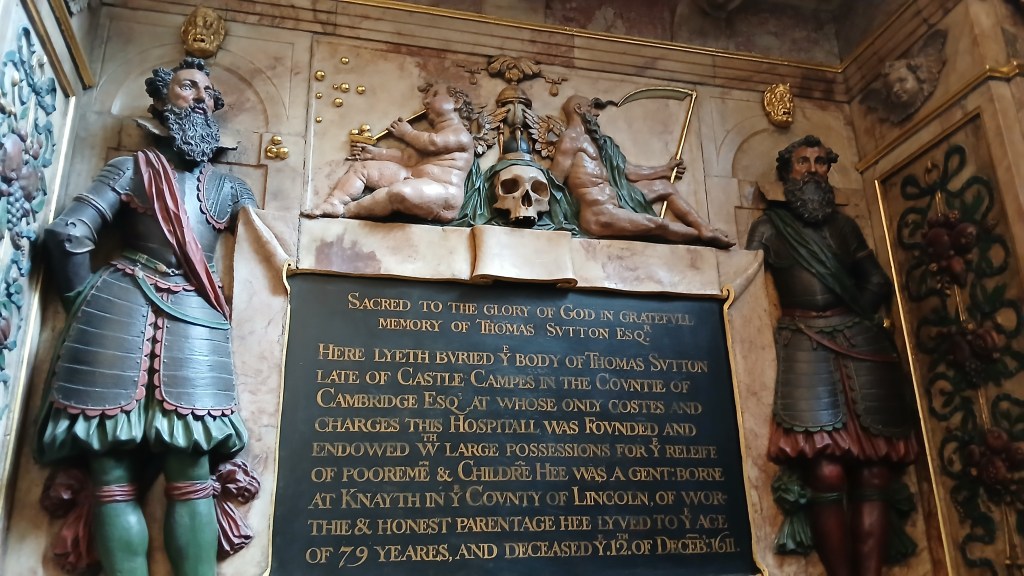

The history of the Charterhouse Chapel is intertwined with the Charterhouse itself. In 1348, land which is now Charterhouse Square was used as an emergency cemetery to bury victims of the first Great Plague, which claimed the lives of 60% of the population of London. Later a chapel was built as a place of prayer for the souls of the dead. When London was finally free of the plague, the then Bishop of London founded a Carthusian monastery, known as Charterhouses, on the site. This thrived until 1538 when Henry Vlll’s Act of Supremacy led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Thereafter the chapel was used to store Henry’s hunting and jousting equipment. The lovely entrance to the chapel was the last phase of the Carthusian building, completed in 1521 and therefore only used as part of the chapel for 17 years. However, it was later adapted for use as a private chapel for a Tudor mansion, built from the ruins of the monastery. Then in 1611 Thomas Sutton, a civil servant and businessman, bought the Charterhouse to establish a school and ‘hospital’ (almshouses) for 40 ‘poor boys’ and 80 ‘poor brothers’. The ‘brothers’, elderly single people, still occupy the almshouses, which in 2017, opened its doors to include female residents. The chapel houses a magnificent memorial to Thomas Sutton.

Sources: thecharterhouse.org; nationalchurchestrust.org

Lincoln’s Inn Chapel

The most striking aspect of this chapel is the rib-vaulted ceiling of the undercroft. The current chapel was completed in in 1623, replacing the original chapel of the Bishops of Chichester, part of the Bishops’ Palace. It was a tradition of chapels in Bishops’ Palaces to be built above an undercroft, and this one is spectacular. The poet John Donne laid the foundation stone in 1620 as preacher of the Inn at that time. The chapel bell, cast in 1613, also has a connection with Donne. By ancient tradition, the bell is tolled at midday on the death of a bencher of the Inn. This practice is said to have inspired Donne’s poem ‘No Man is an Island.’ which concludes with the line ‘And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ In the 18th century, the undercroft became known as a place for mothers to leave babies if they couldn’t care for them. These ‘foundling’ children were initially cared for by the Inn and given the surname Lincoln. The stained glass of the East window comprises the Coats of Arms of the Treasurers of the Inn, including that of William Pitt the Younger, Treasurer in 1794 and future Prime Minister. The chapel holds Sunday services during ‘legal terms’ and is licensed to perform weddings and baptisms for those ‘with a connection to the Inn.’

Sources: livinglondonhistory.org; nationalchurchestrust.org

St Etheldreda’s Chapel, Ely Place

The chapel of St Etheldreda is all that remains of the London Palace of the Bishops of Ely. Around 1250 John le Francis, bishop of Ely, obtained a licence to build a chapel on land owned by St Paul’s Cathedral. Completed in 1290, the London palace grew up around the chapel, extending to 58 acres of farmland and gardens. So why did bishops from Ely and Chichester (Lincoln’s Inn Chapel) have palaces in London? From the 13th century, England’s bishops established households (albeit on a grand scale) in London in order to attend Parliament as many of them held civil, as well as clerical office. St Etheldreda, born about AD630, was the daughter of a Saxon king of East Anglia who founded Ely cathedral in Cambridgeshire. The chapel is unusual because it is a ‘double decker’ chapel, one built on top of the other. The upper chapel was the bishop’s private chapel, and the crypt or undercroft was a place of worship for local people. However, there is a theory that only the upper chapel was used as a church and the undercroft had other purposes. It’s possible that that it was divided into two or more rooms; there is evidence of a well and two chimneys within the walls, which suggests domestic use. Since the late 1800s the crypt has been used continually as a place of worship. My photos are of the atmospheric lower chapel with its beautiful modern stained glass windows.

Source: Booklet in the Chapel

Lady Chapel, St Bartholomew the Great

St Bart’s at Smithfields is another wonderfully atmospheric ancient church and on a recent visit, I came across the Lady Chapel. One of the miracles recorded in the Book of the Foundation of St Bart’s tells the story of a vision of the Virgin Mary in the 12th century to Cannon Hubert, one of the Austin (Augustine) Cannons living in the priory. She allegedly accused the cannons of laxity in devotion and worship to her and her Son Jesus. It was decided to build a much larger Lady Chapel at the East End of the church; chapels dedicated to saints are usually located in a side aisle. In the Reformation, Henry Vlll allowed St Bart’s to remain as a church and priory because of the attached hospital, but the Lady Chapel was separated from the main church and converted to commercial premises. By the 1700s it was a printer’s workshop and it was here that a young Benjamin Franklin began an apprenticeship as a trainee typesetter. The Lady Chapel was restored to the church in 1897 to be used again for worship and church services. A Eucharist service took place in the Lady Chapel on 21st September, in the week which celebrated Founder’s Day, marking 9002 years since the church was founded by Prior Rahere, councillor to Henry ll. The painting above the altar is of ‘Our Lady of Smithfield.’

Source: greatstbarts.com; livinglondonhistory.org