These are some rather unusual and interesting things I’ve found on my travels around the capital. One is a temporary installation, but I’ve included it because its spectacular! I’ll save that till last, meanwhile, here’s

A Sauna in a Church

Yes, really! The Finnish Church in Rotherhithe, South London is ‘a welcoming church and community for all the Finns who live in Great Britain and Ireland (either permanently or temporarily), as well as their friends and family – and all friends of Finland!’ As well as a sauna in the basement, there’s also a café and a shop selling Finnish delicacies and a hostel offering accommodation to tourists and backpackers. The church has a long history of pastoral care, having been established as the UK branch of the Finnish Seamen’s Mission in 1882 and continuing today as a community hub. All info from the church website: lontoo.merimieskirkko.fi, which I think translates as: Londonseamanschurch.fi!

No one was using the sauna at the time!

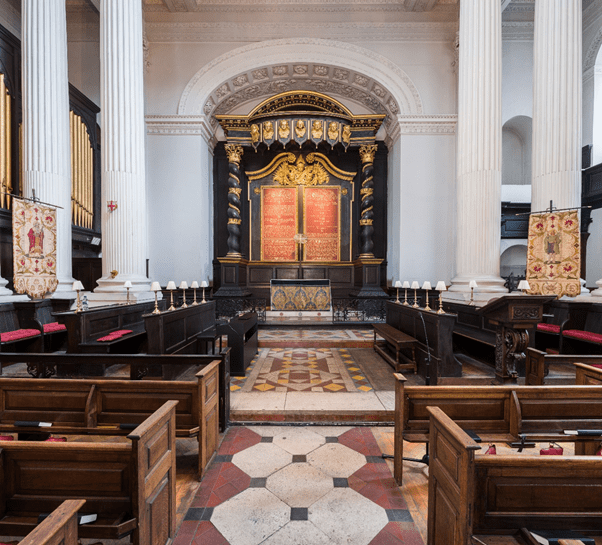

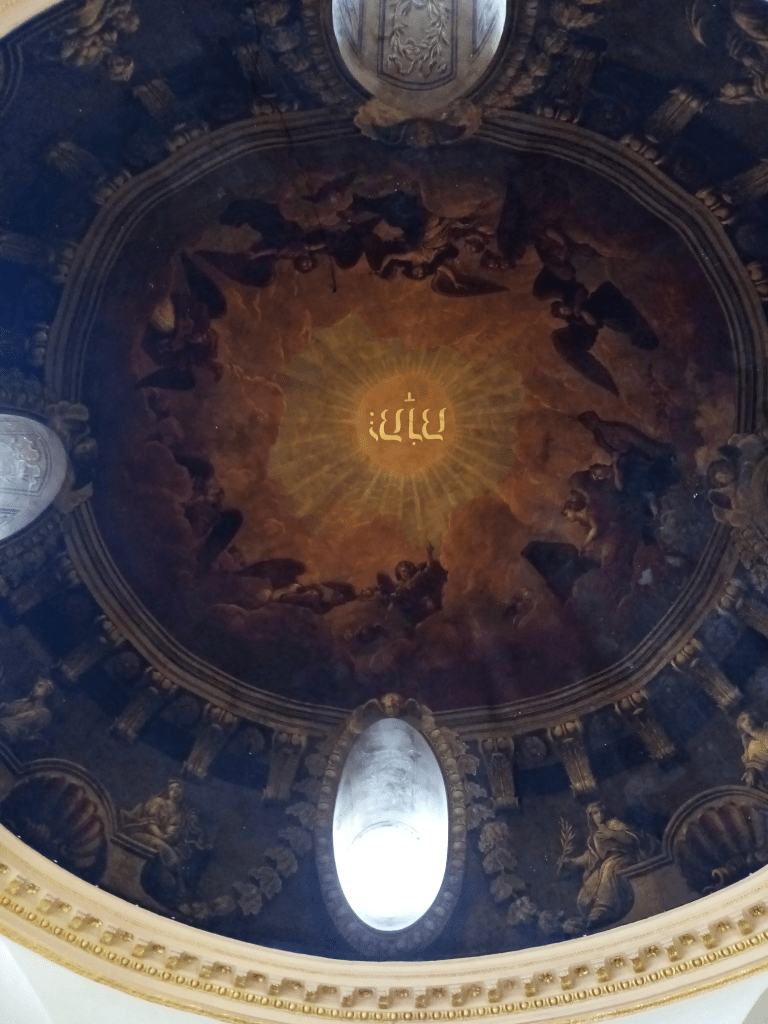

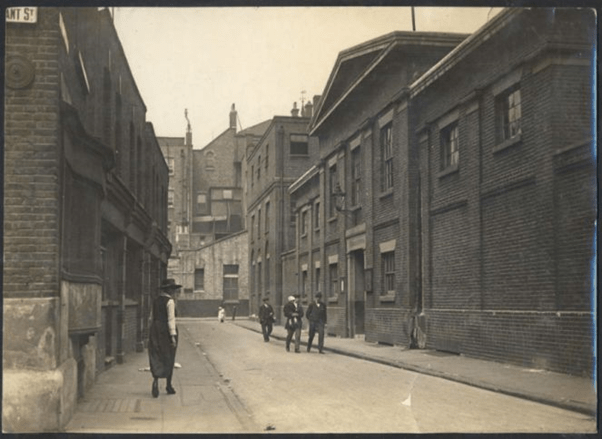

St Magnus the Martyr

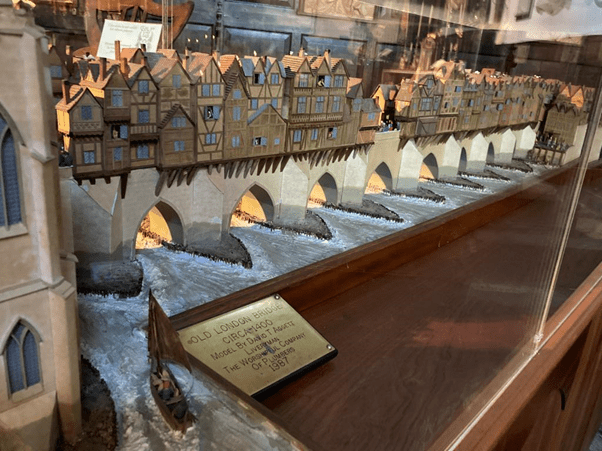

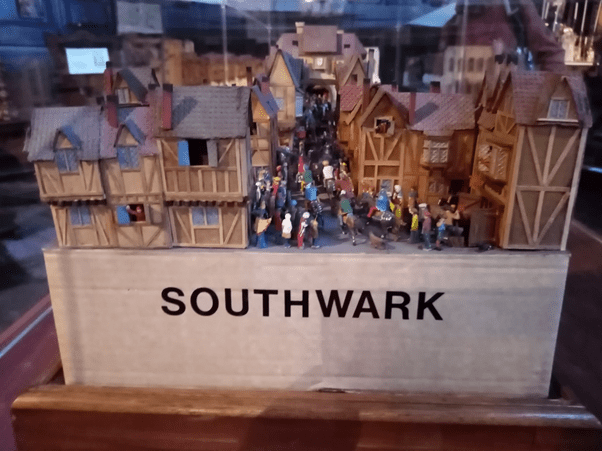

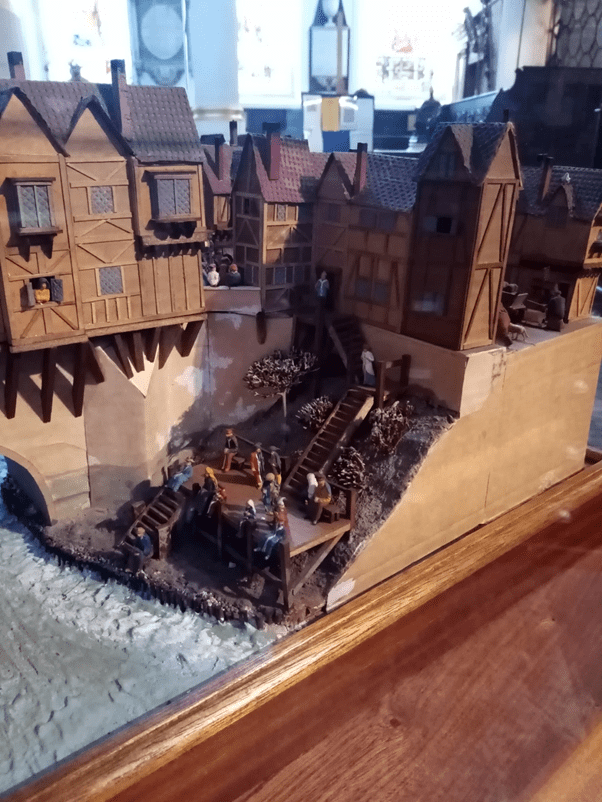

This church, now on Lower Thames Street, used to be right on the North bank of the River Thames and was the gateway to the bridge that spanned the River there from 1176 to 1831, old London Bridge. People had to pass through the churchyard to set foot on the bridge, consequently, it got very crowded, as this was London’s only bridge. When a new bridge was commissioned in the 1830s it was built further upriver from where a succession of bridges had spanned the Thames since Roman times. In 1987 a liveryman from the Worshipful Company of Plumbers decided to make a scale model of the old London Bridge to display in the church, a must-see if you’re in the area. David Aggett’s wonderful model has over 900 tiny people crammed onto the bridge and dozens of buildings including shops, houses and a chapel in the middle. The model also captures the 20 arches that would have held its weight, and which created the narrow channels of swirling water, where brave boatmen would try to ‘shoot the rapids’, and some lost their lives. You can see a boat just coming up to the first arch.

Information from http://www.london-walking-tours.co.uk/old-london-bridge

This is a piece of wood from old London Bridge

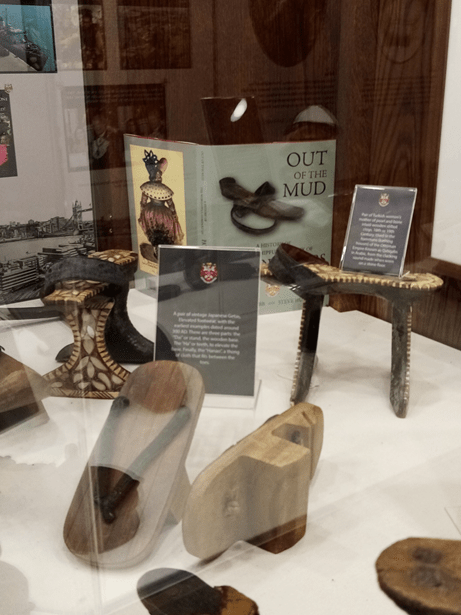

St Margaret Pattens

This church on Cheapside is dwarfed by its near neighbours, including the giant Walkie Talkie building. It changed from a parish church to a Guild Church in 1954, due to falling church attendances in City churches (because fewer people lived in the City). Guild churches hold midweek lunchtime services serving a regular congregation of office and shop workers in the area. The Interesting Thing about St Margaret is its association with The Worshipful Company of Pattenmakers since the 15th Century. Pattens are raised wooden soles which fit onto shoes to keep the wearer’s shoes and skirts out of the mud of the unpaved streets. The trade and manufacture of pattens was carried out in and around Rood Lane, where the church now stands, and St Margaret’s adopted ‘Pattens’ as there were several churches dedicated to the saint at the time. The practice of wearing pattens went out of fashion in the 19th Century as streets gradually became paved. The WC of Basketmakers is also associated with the church, because, you guessed it, their trade was carried out in the vicinity. Must have been a very different street scene, now it’s just endless coffee shops (I spotted Greggs, Pret, Starbucks and Black Sheep Coffee.) These are the display cabinets of pattens and baskets. My favourites are the pair on stilts! Information from Church leaflet and display boards

Children’s pattens

Matching shoes and pattens

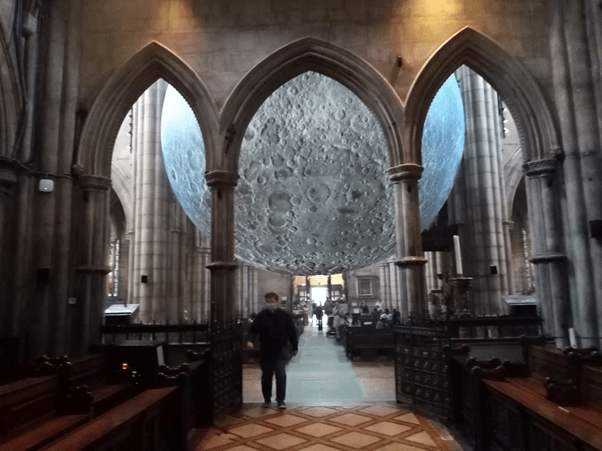

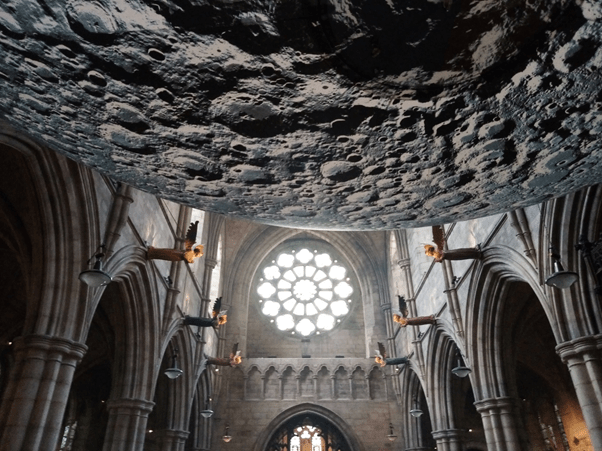

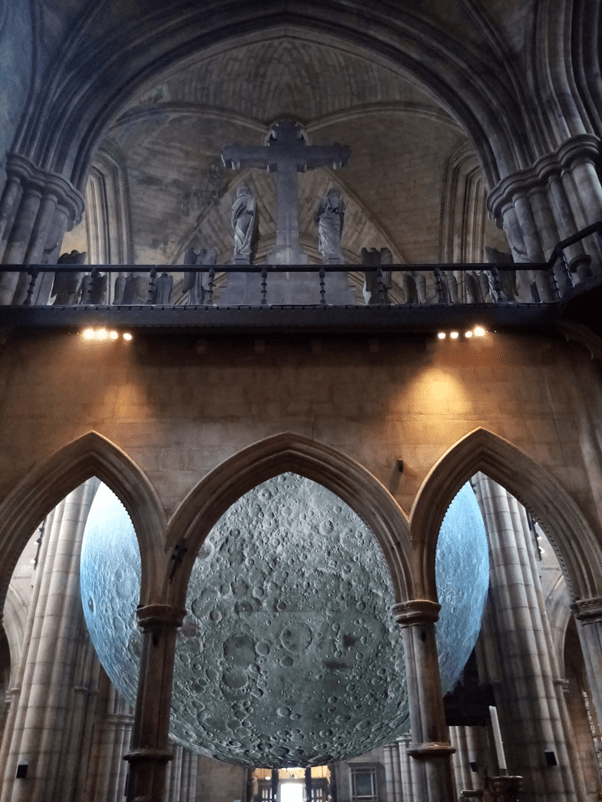

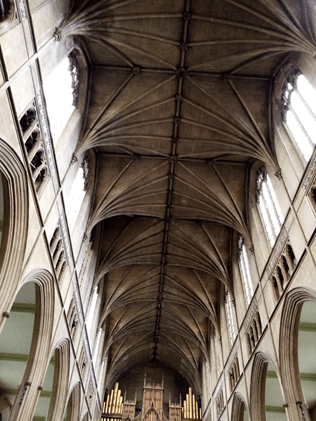

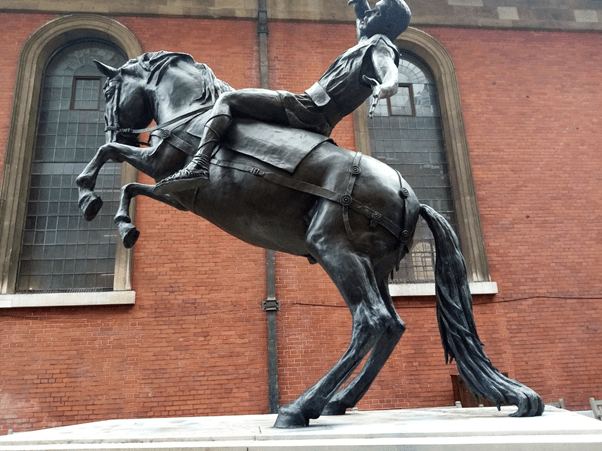

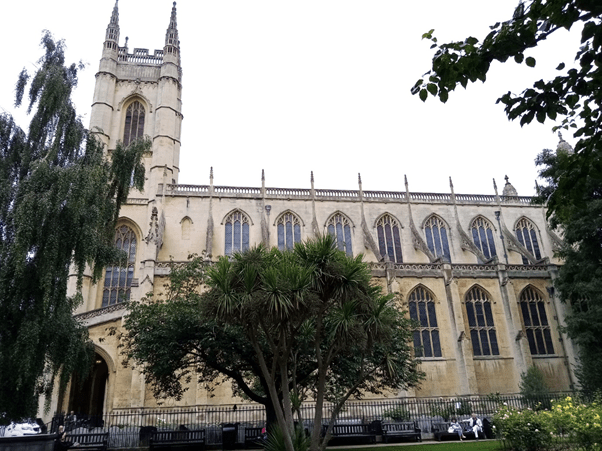

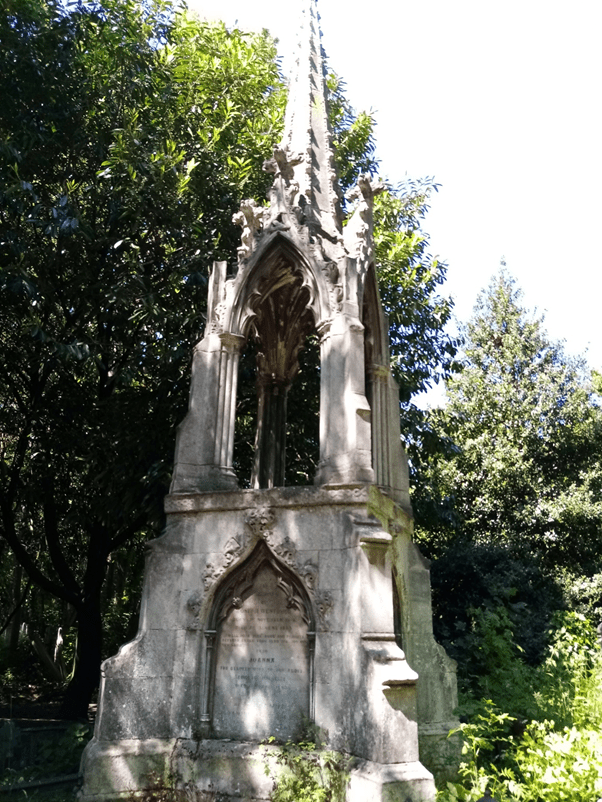

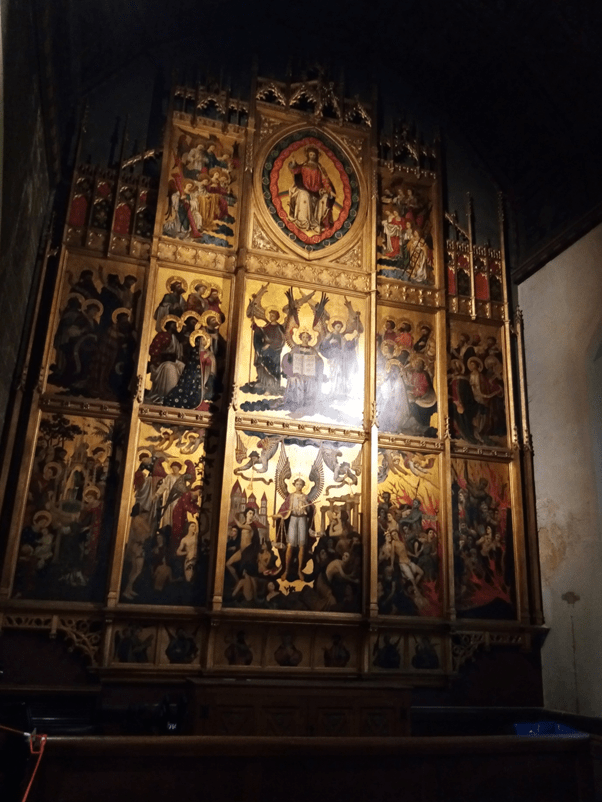

St John the Baptist, Shepherd’s Bush

This church hosted the Museum of the Moon in August, I was so pleased to be able to visit, it’s just so beautiful. ‘Measuring 7 metres in diameter, the moon features detailed NASA imagery of the lunar surface. At an approximate scale of 1:500,000, each centimetre of the internally lit spherical sculpture represents 5km of the moon’s surface.’ The moon sounds like a rock star; its website (my-moon.org) gives its Tour Dates! These include Durham, Chichester and Wells Cathedrals and Bath Abbey and it also appears in USA, Canada and Europe The website says ‘there are several moons touring simultaneously’, which I found very funny for some reason. This church is an excellent showcase for the moon, being in the Gothic style and very atmospheric. It’s a Victorian, Grade 1 Listed building, which means it can’t be altered in any way, inside or out. Mesmerising!