London has been welcoming immigrants for hundreds of years due to the migration of people groups wanting better lives for their families or seeking refuge from persecution, war and natural disasters. This month I’m going to look at London churches which serve (or have served) European communities, and talk a little bit about their histories. I really enjoyed researching the churches this month!

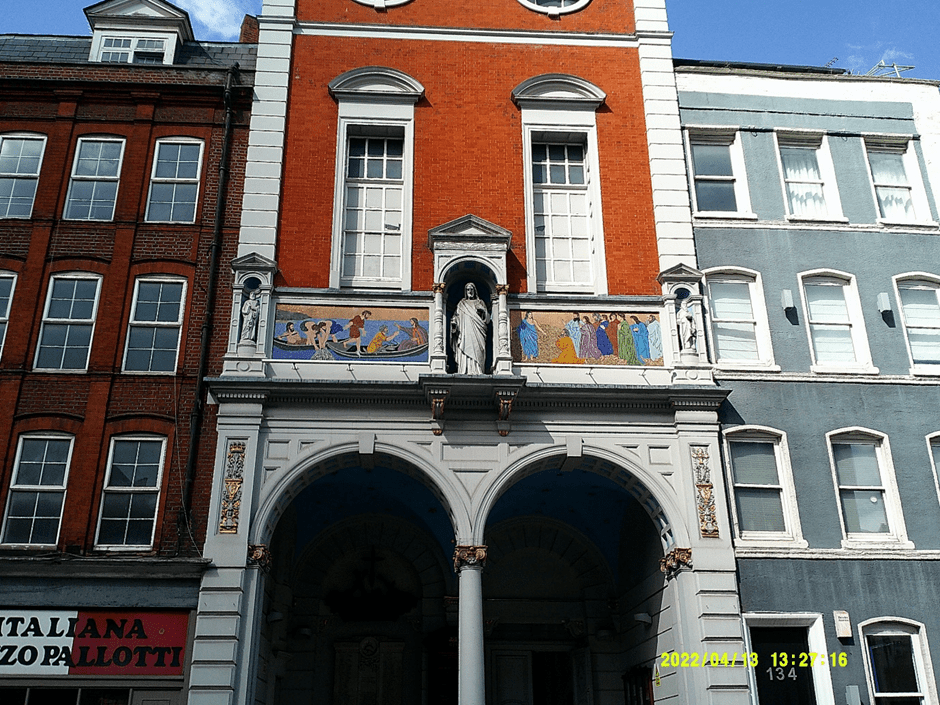

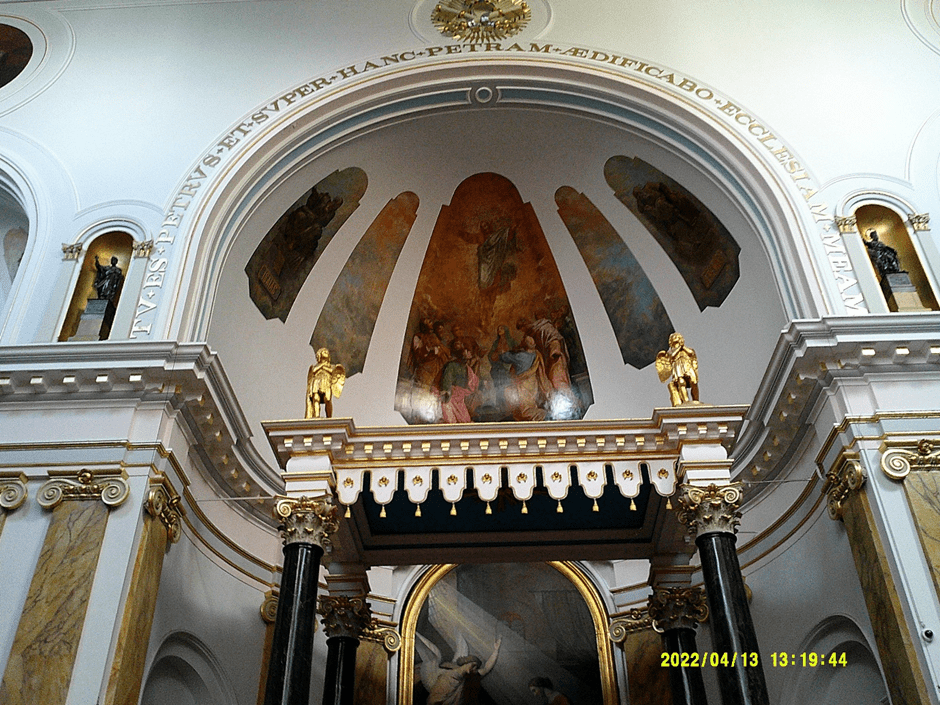

St Peter’s Italian Church, Clerkenwell

This gem of a church, sitting between shops and offices in Clerkenwell Road, was opened in April 1863 as ‘The Church of St Peter of all Nations.’ At the time it was the only church in Britain designed in the Roman Basilica style, and when I stepped inside, it felt like I was stepping into a church in Rome; breathtakingly beautiful decorations and artwork. St Peter’s was designed by Irish architect Sir John Miller-Bryson and modelled on the Basilica San Crisogono in Rome. The church was built to serve the growing number of Italian immigrants in the Clerkenwell area, known as ‘Little Italy.’ The church is under the control of the ‘Pallottines’, a Roman Catholic Society, founded in 1835 by Saint Vincent Pallotti, and it was he who commissioned the church. St Peter’s provides services throughout the week in Italian and English, and plays an important part in the life of the community, a focal point of the annual processione held in July. There are a number of Italian cafes, restaurants and barbers’ shops up and down Clerkenwell Road.

Source: Wikipedia

The Dutch Church, Austin Friars

This church has an interesting history. On this site there was an Augustine Friary, established in the 1260s, consisting of a church, accommodation for 600 friars and a garden with an orchard, quite a substantial property. The friary played an important role as a centre for religious education, not just for English students but by foreigners living in London, mostly Italians and Germans. Following the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1538, Henry’s advisor, Thomas Cromwell bought up the friary land to build for himself one of the largest mansions in London. Cromwell’s meteoric rise in fortunes was followed by an equally meteoric fall from the King’s favour and he was executed in 1540, after which the mansion and lands were sold off. So what’s the Dutch connection? In July 1550, King Edward VI, son of Henry VIII, issued a Charter in which he granted European Protestants escaping persecution in Catholic Europe the freedom to hold their own church services. He gave part of the (still standing) church at Austin Friars to Dutch and French refugees resident in London. The French Protestants relocated to another church (more on that in the next section) but the Dutch Church still holds the 1550 Charter. The original monastery church was destroyed in a World War 2 air raid in 1940; and on 23rd July 1950, ten-year-old Princess Irene of the Netherlands laid the foundation stone of the new church, commemorating 400 years since the 1550 Edward VI Charter. The new church was completed in 1954, built in the style of Protestant churches in the Netherlands.

Sources: Booklet in the Church; squaremilehealthwalks.wordpress.com

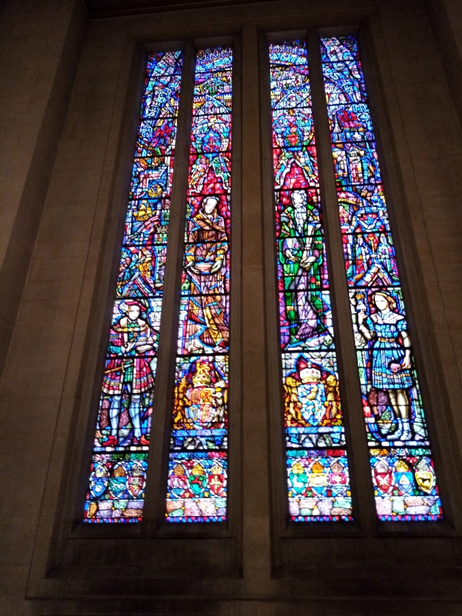

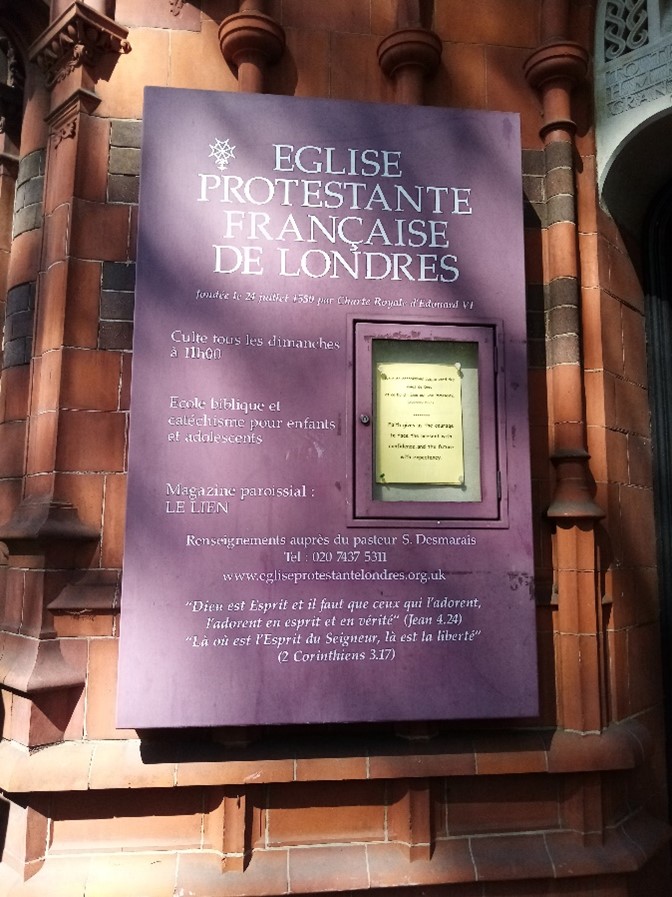

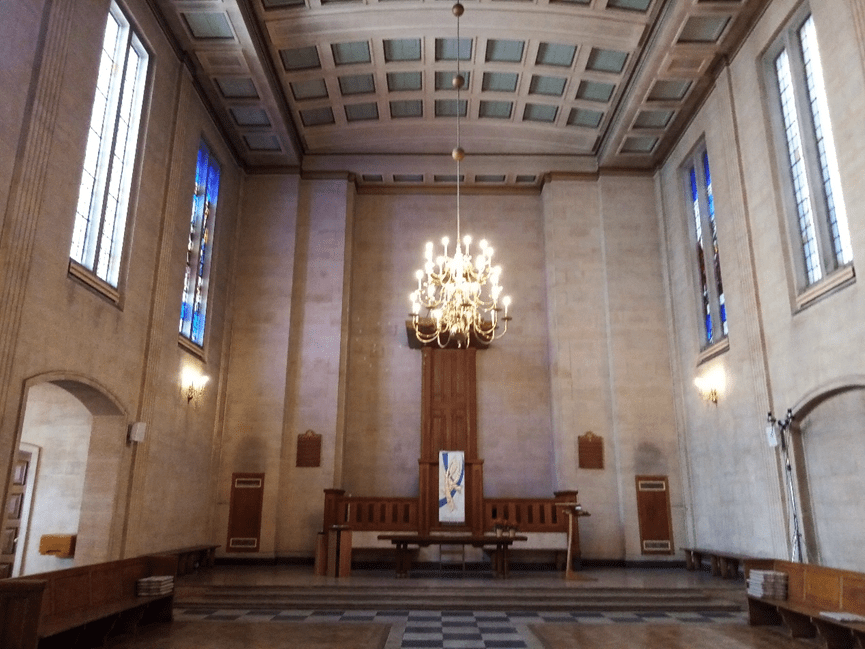

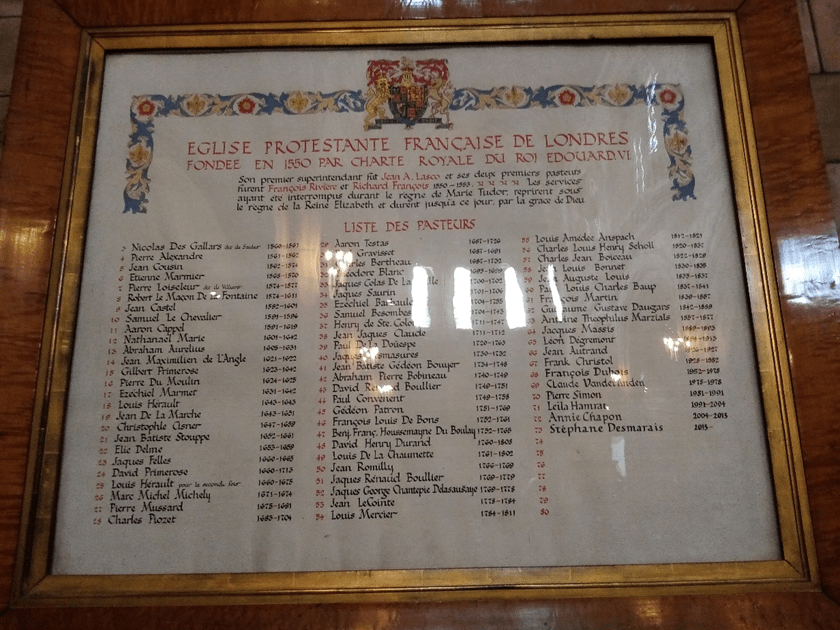

The French Protestant Church, Soho Square

When I arrived outside this church it was clearly closed, and I dithered whether to cheekily press the buzzer marked ‘Church’ and request entry for a quick look inside. Suddenly a side door opened and a man came out, beckoning to another man waiting outside (who I hadn’t noticed) to come in. I asked him if I could possibly to come in to take a few photos, to which he agreed, saying that he was the Pastor! I thanked him profusely (in French) and scurried round as quick as I could! The French Protestant Church has served the French-speaking community in London since 1550, founded by the Edward VI Charter mentioned above. The Soho Square building was erected in 1891, replacing the first church under the Charter in Threadneedle Street, and it’s now the last remaining Huguenot church in England. The Huguenots were French Protestants who suffered persecution for over 200 years in France because of their Reformist and Calvinist beliefs. Many thousands fled to England following the English Reformation and in 1681 King Charles II formally offered them his royal protection. The Huguenots were mainly skilled craftsmen and professional people, famous for silk weaving and also highly skilled clock makers, metal workers and silversmiths. The largest settlement of Huguenots was in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green.

Sources: Wikipedia; thehistoryoflondon.co.uk

St George’s German Lutheran Church

This church is now owned by the Historic Chapels Trust. It is the oldest surviving German church in Britain, however, it is now closed for regular Sunday worship except for occasional services by the German community. The main use of the building is for concerts, lectures and historical study. Next door to the church is ‘St George’s German and English schools supported by voluntary contributions.’ St George’s was established in 1763 as a Christian centre for German Lutheran immigrants who worked in the East End in various industries: sugar refining and the baking and meat trades. The First World War was a disruptive and unsettling time for the community; men of military age were interred and older men and women were expelled from the UK. The then Pastor and his wife were expelled in 1917, returning in 1920, but amazingly, church services continued throughout both World Wars and beyond, until 1996. During the Second World War, the pastor at that time, Julius Rieger, assisted Protestant Christians of Jewish descent to escape from Germany to the UK. The theologist and anti-Nazi activist Dietrich Bonhoeffer was associated with St George’s as pastor of nearby German Reformed St Paul’s Church between 1933 and 1835. This church was closed when I visited; the interior photo is from the church’s website. St George’s is just outside the old City Walls, where the City ends and the East End begins at Whitechapel.

Source and Interior Photo: St George’s German Lutheran Church website