These are some more Blue Plaques found on buildings in central London, commemorating Christians who have lived out their Christian faith in obedience to God and for the benefit of others. Three of them are relatively unknown. In alphabetical order:

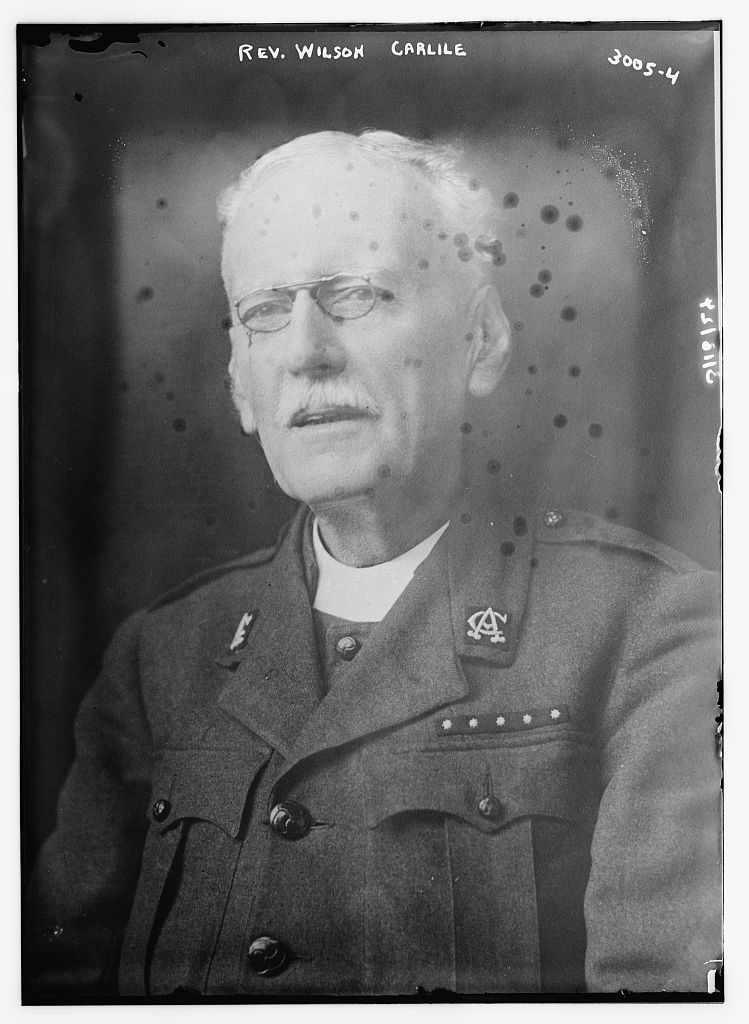

Wilson Carlile 1847 – 1942

Photo: Me

Photo: Richard Arthur Norton at en.wikipedia

Wilson Carlile was something of a child prodigy, being gifted musically and at learning languages. He joined his grandfather’s business and by the age of 18, had almost total control, due to his grandfather’s failing health. He determined to be a successful, ambitious businessman, and by 25 he had made his first million in today’s money. But a great depression which began in 1873 meant that he lost almost all the wealth he had acquired, leading to a mental and physical breakdown. Confined to bed, he began to question the purpose and meaning of his life and the chance reading of an evangelical work, Mackay’s Grace and Truth, caused him to turn his life around as he began to believe in ‘the crucified and risen Lord…..He touched my heart, and old desires and hopes left it. In their place came the new thought that I might serve Him and His poor and suffering brethren.’ (Wiki). Fast forward 9 years, during which time Carlile worked with evangelist DL Moody, musical director Ira Sankey, and the Salvation Army, and gained an understanding of mission and evangelism, to 1882, when he formed the Church Army. As a curate in wealthy Kensington, Carlile wanted to break down the barriers between the rich and poor, so he resigned his curacy to work in slum areas, ‘to share the Gospel with people who wouldn’t dream of setting foot inside a church’. (Wiki). He had the idea of using ordinary, non-ordained men (and controversially, women) to train as evangelists to work among the poor and marginalised. The idea of a spiritual ‘army’ was popular at the time as a metaphor for the fight against spiritual forces of evil, so the Church Army was born. Carlile always worked under the authority of the Church of England, ensuring that evangelism carried out in a community always had the approval of the parish priest, and in a prison or other institution, by invitation of the chaplain. Carlile met with resistance from top level Church of England officials because of his unorthodox methods, but gradually the Church Army gained the respect of the Church, partly because of Carlile’s great respect for the Church! By 1925, the Church Army was the C of E’s largest home mission society.

Reverend Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton 1885 – 1972

Photo: Me

Photo Author: Filibertus at vis.wikipedia

Tubby Clayton was a Church of England ordained priest and served as an army chaplain in World War 1 in France. He and another chaplain, Rev. Neville Talbot, opened a rest home for wounded soldiers at Poperinge, Belgium in 1915 called Talbot House (named for Neville’s younger brother Gilbert, who was killed earlier in 1915). Poperinge was a transfer station where soldiers were billeted on their way to and from the battlefields of Flanders, and the chaplains’ idea was to provide an ‘Everyman’s Club’, where all soldiers would be welcome, regardless of rank. It became known as Toc Aitch, this being signal terminology (a sort of NATO phonetic alphabet) for TH. In 1920 Clayton and his fellow leaders were inspired to set out The Four Points of the Toc H Compass:

- Friendship – ‘To love widely’

- Service – ‘To build bravely’

- Fair-mindedness – ‘To think fairly’

- The Kingdom of God – ‘To witness humbly’

At first I thought these four ‘compass points’ were a bit random, but now I think they make sense, these are things that all Christians should aspire to, aren’t they? After the war, other Toc H houses were established in Kensington, Manchester and Southampton, and later, a women’s league. From 1922 to 1962, Clayton was vicar of All Hallows-by-the-Tower (one of my favourite churches) and began working with the East End poor. Following the Blitz in 1940, he played a primary role in fundraising for the restoration of the badly damaged All Hallows and for the devasted East End. He was also chaplain to the British Petroleum Company. The Toc H legacy lives on today in Christian facilities and activities: youth centres, residential holidays for special groups, entertainment for care home residents, and reconciliation work with disparate groups in society.

Elizabeth Fry 1780 – 1845

Photo: Me

Image: Wikipedia (in public domain)

Let’s go back in time one hundred years to the inspiring Elizabeth Fry. Born into a wealthy Quaker family, she married Joseph Fry, also a Quaker and a banker. In her teenage years, Elizabeth was inspired by William Savery, an American preacher, abolitionist and an advocate of social justice. She felt that God was calling her to devote her life to working for the poor and socially excluded, an unusual ambition at the time for a wealthy married woman, who would have been expected to spend her days in leisure pursuits and the raising of children. Elizabeth actually did have 11 children, presumably cared for by an army of nannies! Invited to visit Newgate Prison in the City of London when she was 33 years old, she was horrified by the conditions and particularly the overcrowded, filthy cells of women and their children. She was also struck by the injustice of their situation; many of the women were being held without trial. Elizabeth returned to the prison the following day bringing food and clean clothes for some of the prisoners, but she knew she had the means to do more. Despite financial difficulties in the Fry bank, she funded a school for prison children and offered their mothers opportunities to learn needlework, knitting and cooking so that they could earn their own living on release from prison, thus ending the cycle of imprisonment for non-payment of debts (Newgate was a Debtors’ Prison where Charles Dickens’ father was incarcerated.) Elizabeth set up the ‘Association for the Reformation of Female Prisoners in Newgate; a Nursery School; and the ‘Brighton District Visiting Society’, a forerunner to the Health Visitor scheme. She believed that education was a route out of poverty and that people did not choose to beg or steal to survive but needed support to improve their lives. Queen Victoria was impressed by Elizabeth’s concern and determination and provided funding for several of her causes.

Lincoln Stanhope Wainwright 1847 – 1929

Photo: Me

Image: Alan Patient of plaquesoflondon.co.uk

Lincoln Wainwright was the Assistant Priest and then Vicar of St Peter’s Church at London Docks for 56 years. Being privately educated at Radley and Wadham Colleges Oxford, he could have taken the ‘living’ at any wealthy parish in England but chose to live among the poorest Londoners in the Dockland slums. Wainwright devoted himself to providing the local people with ‘ragged schools’, working men’s clubs and medical facilities, at a time when there was no Welfare State, and education and medical care had to be paid for. He frequently gave his own food to poor parishioners, and on one occasion, his own clothes and shoes. Working on the docks was a precarious lifestyle, particularly for unskilled labourers who would wait each day to be chosen for the most arduous jobs of unloading from the ships, for a pittance of a wage. Only the strongest and fittest would be offered work and families could literally starve to death if Father didn’t get regular work. In the 1880s there was a dock strike and Wainwright supported destitute families financially and emotionally as best he could. When he died in February 1929 one of his parishioners wrote: ‘Dockland was washed with tears because this tiny but indomitable figure, shabby, untiring, spendthrift of love, would not serve them on Earth anymore’. I think it’s a sad legacy that his name is misspelt both on the Blue Plaque and the stained-glass window in the church, but there are many tributes to his life of selfless devotion to the poor.

I think my favourite of these Blue Plaque People has got to be Lincoln Wainwright; he wasn’t the founder of an organisation, he wasn’t a catalyst for change, he wasn’t a major fund raider for some big social project, his name doesn’t appear on any building. But he faithfully served the poorest of communities his whole life, not asking for, or expecting recognition. That was his legacy.

Thanks as always to Wikipedia for information on Carlile, Clayton and Fry, and to the delightfully-named stchrysotoms.wordpress.com for Wainwright.

All photos and images are in the public domain.