Another four cosy church cafes visited in February, this time to escape the torrential rain rather than the cold! Walking from Victoria Station to the last two cafes, I passed at least 25 other cafes, restaurants and coffee shops, both chains and independents, so it’s good to visit those located in or connected with churches – there’s a lot of competition for business in tourist areas.

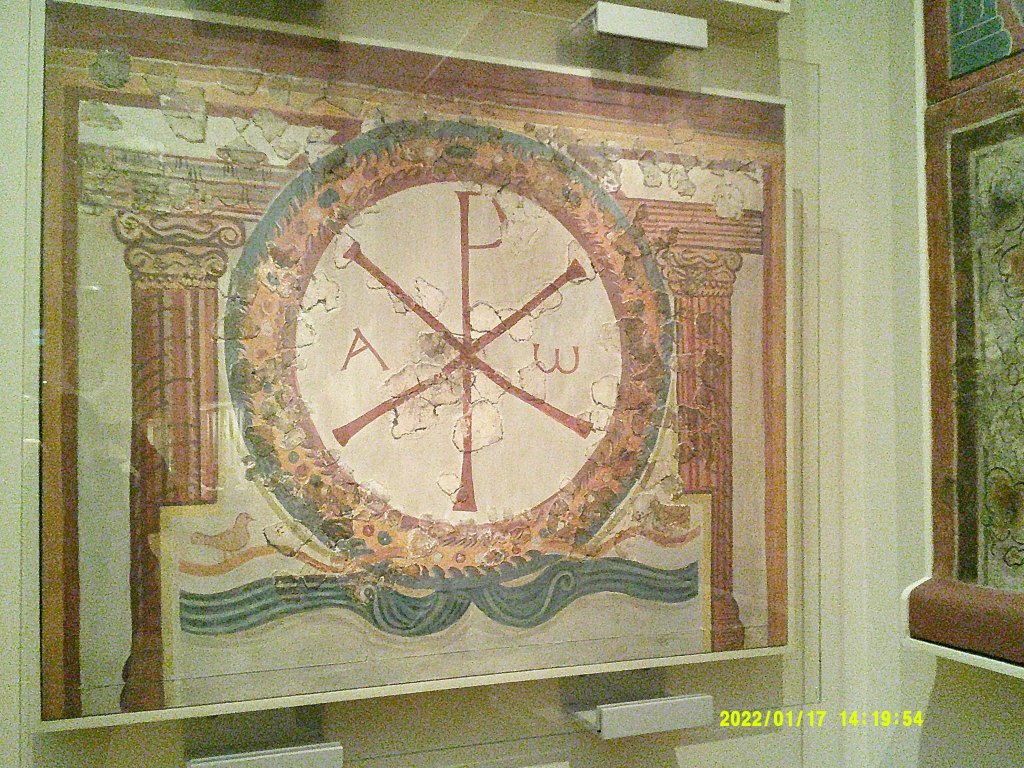

St Paul’s Crypt Café

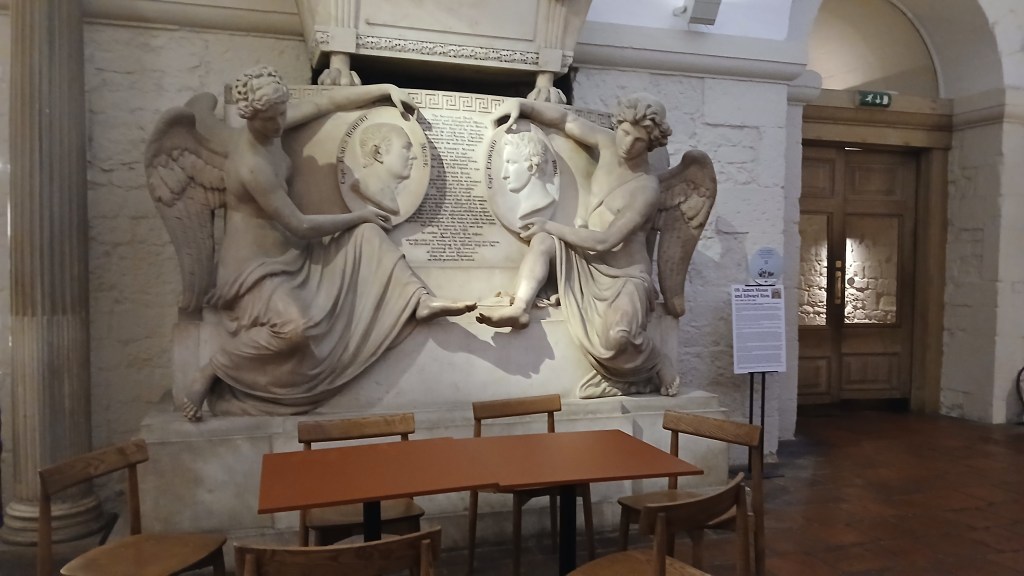

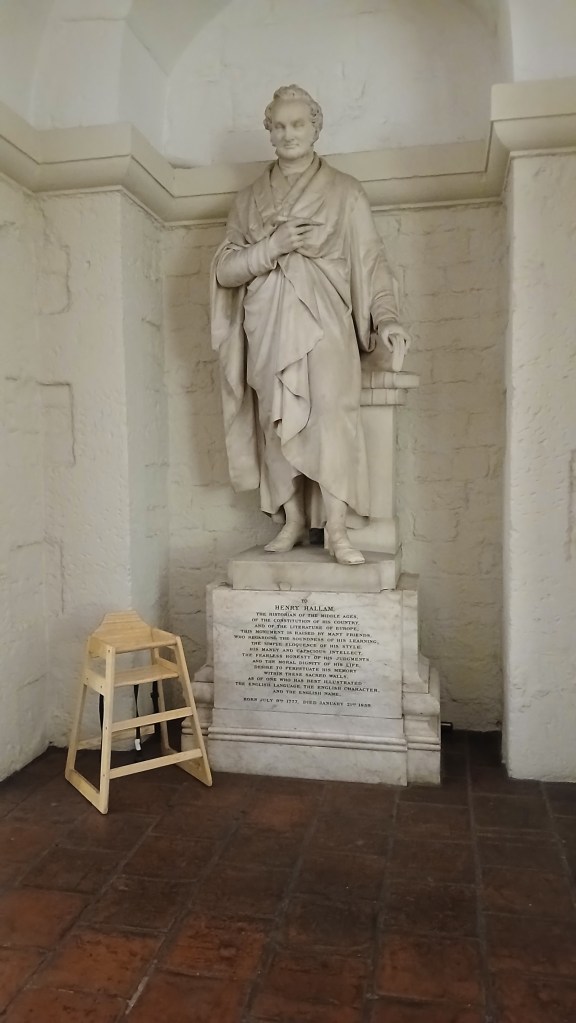

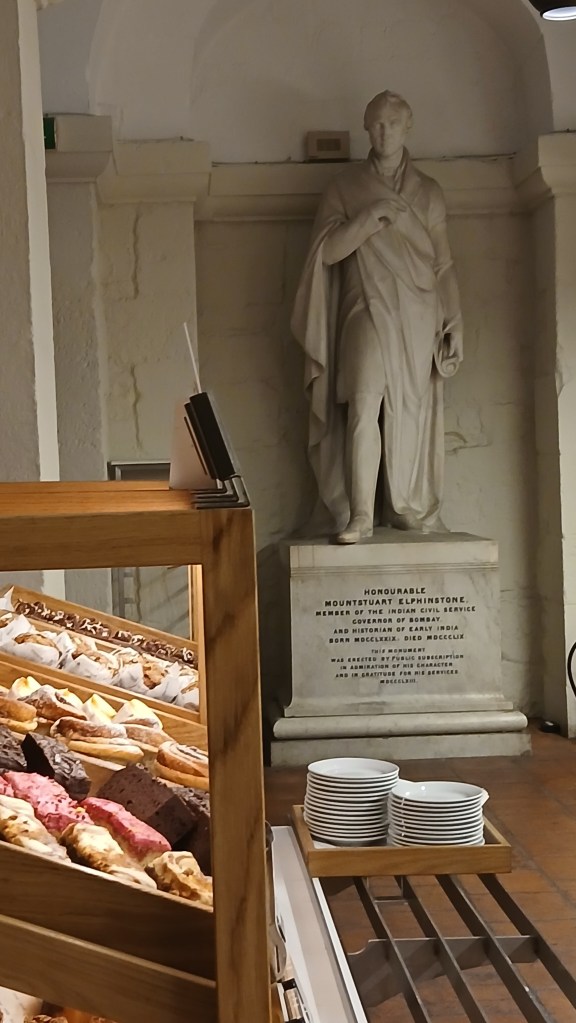

This café is situated beneath St Paul’s Cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren’s 17th century masterpiece which replaced the former church destroyed in the Great Fire. The crypt is the largest in Europe and in addition to the café it houses the Cathedral shop and a large seating area for school groups. The café and shop can be accessed from the North Crypt door so customers don’t need to pay to go into the Cathedral itself (although of course the Cathedral is a must-visit.) Going down to the crypt is an interesting experience on its own, with statues and monuments in situ occupying the alcoves and walls, providing an atmospheric space to sip your cup of coffee. The café serves hot and cold snacks and light lunches as well as all the beverages. I didn’t have any food this time but I’ll probably pop back when next visiting this part of the city. Note: the highchair in the second picture really was exactly in that position!

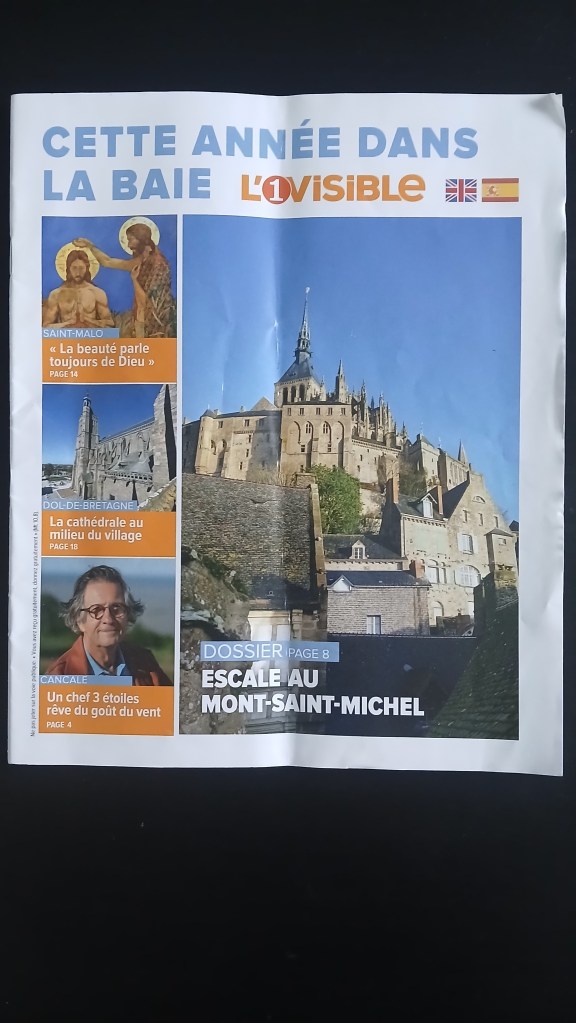

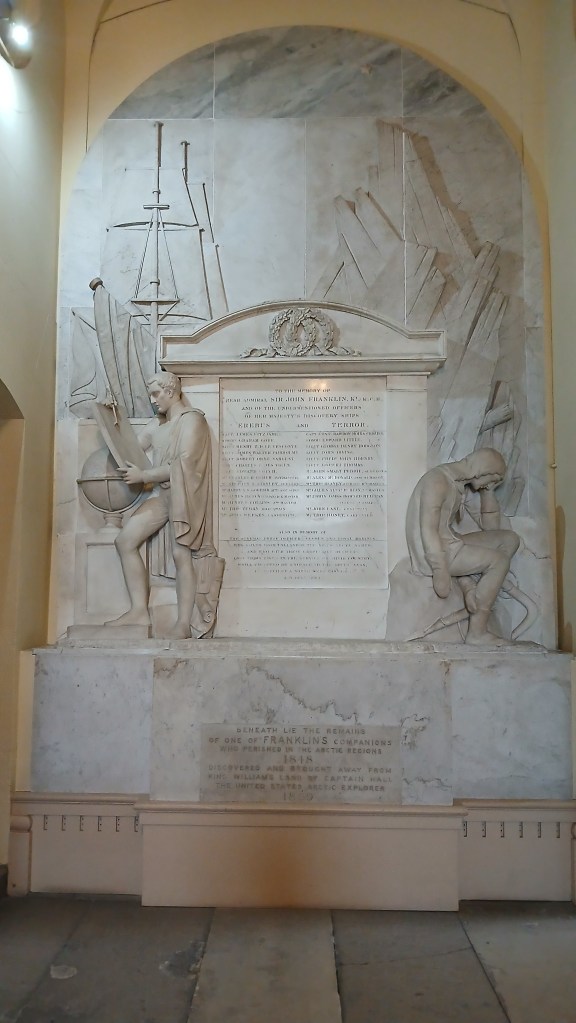

St Martin-in-the-Fields, Café in the Crypt

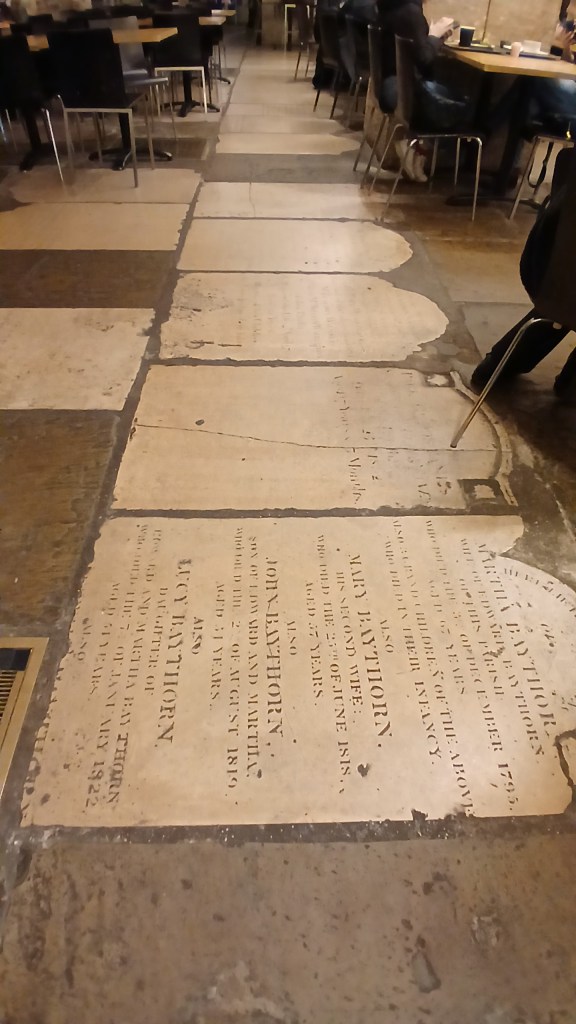

The Café in the Crypt below St Martin is a long-established and very popular eating place, just off Trafalgar Square. A circular lift inside a spiral staircase takes you down to the crypt with its shop, brass rubbing centre and the café with its vaulted brick ceilings. The café has secluded alcoves and historic tombstones right under your feet, dating back to when the crypt was a place of burial. It serves substantial breakfasts and lunches and snacks. I thought a freshly brewed flat white and an almond croissant for £6 was exceptional value for this part of London. If I’d wanted a more substantial meal, there was lots of choice, including fish and chips, macaroni and broccoli cheese, and chicken tikka. Also available are hot and cold puddings and fruit. also in the crypt is the Gallery, displaying artwork and monuments from the church above, and this intriguing statue of London’s first Pearly King.

New Acre Café, Westminster Chapel

I visited this café last year when it was closed for a private function. This time there was a conference in the hall but the café was open so I had a latte and chatted to barista Darina, who told me about Church House Café (below.) I’ll repeat here what I wrote about New Acre’s interesting history last year: The area around Westminster Chapel was named ‘The Devil’s Acre’ by Charles Dickens in the 1800s, being a place of crime and extreme poverty. The Chapel established schools, alms-houses for the poor and work schemes for the unemployed, and Dickens was impressed by the way the Christians devoted their lives to the care of the inhabitants of the Devil’s Acre. The café was named New Acre ‘to remind us of the reason that God has put us here today.’ The profits from sales of the coffee sold here, Old Spike Benedict Blend, go directly to support people experiencing homelessness.

Sources: westminsterchapel.org.uk; notice in café

Coffee break

Church House Café

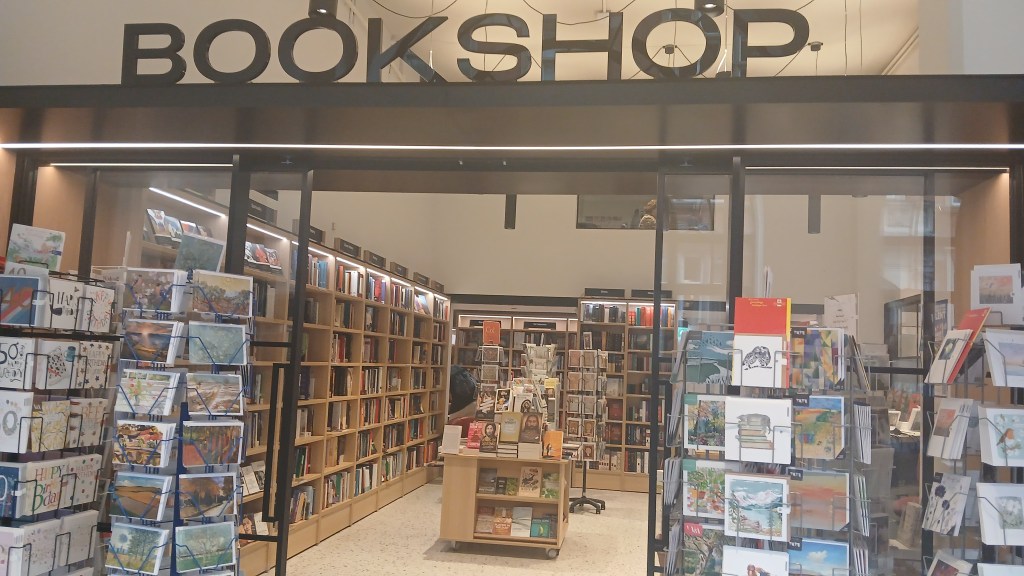

Church House, Westminster is a historic Grade ll listed building located close to Westminster Abbey which today hosts conferences, awards ceremonies and gala dinners in its 19 halls and meeting rooms. In the Second World War the then Prime Minister Winston Churchill relocated the two Houses of Parliament to Church House because of the building’s exceptionally robust construction. The café and bookshop occupy a small part of the building, with the café serving locally-produced coffee and speciality teas, breakfasts, lunches, homemade cakes and pastries. Arriving at lunchtime, I had to make the difficult choice between quiche of the day and a ham and cheese croissant. I’ll have to return and have the quiche another day! The well stocked bookshop is an added bonus with a particularly good selection of children’s books.

Source: churchhouseconf.co.uk