Early summer is so beautiful, all the trees are in full leaf and the flowers are at their colourful best. There are some lovely churches on the edges of the outer London boroughs which have a real country feel, especially when surrounded by greenery. These four are all within half an hour’s drive of my home, but I think I’ll continue this theme next month, exploring churches in other outer London boroughs.

St John the Evangelist, Old Coulsdon

A lovely ancient church on Old Coulsdon Village Green, you can imagine it in years gone by being the centre of village life and there is a row of charming little flint cottages leading to the churchyard to complete the rural picture. The original church dates from the late 13th century, and the tower, chancel and nave were added in the 15th century. As with many of the churches in the London suburbs, St John’s had to be adapted from a small medieval building to one that could cater for a rapidly growing population, as the middle and upper classes moved to the ‘countryside’ (as it was in the early 20th century.) In 1958 the church was extended and modernised, which can be clearly seen in the bottom picture. The south aisle was demolished and much larger aisles, nave and chancel were added at right-angles with the original church. A more recent extension added a kitchen, parish office and all-important toilets!

Sources: southwark.anglican.org; londonchurchbuildings.com

St John the Baptist, Old Malden

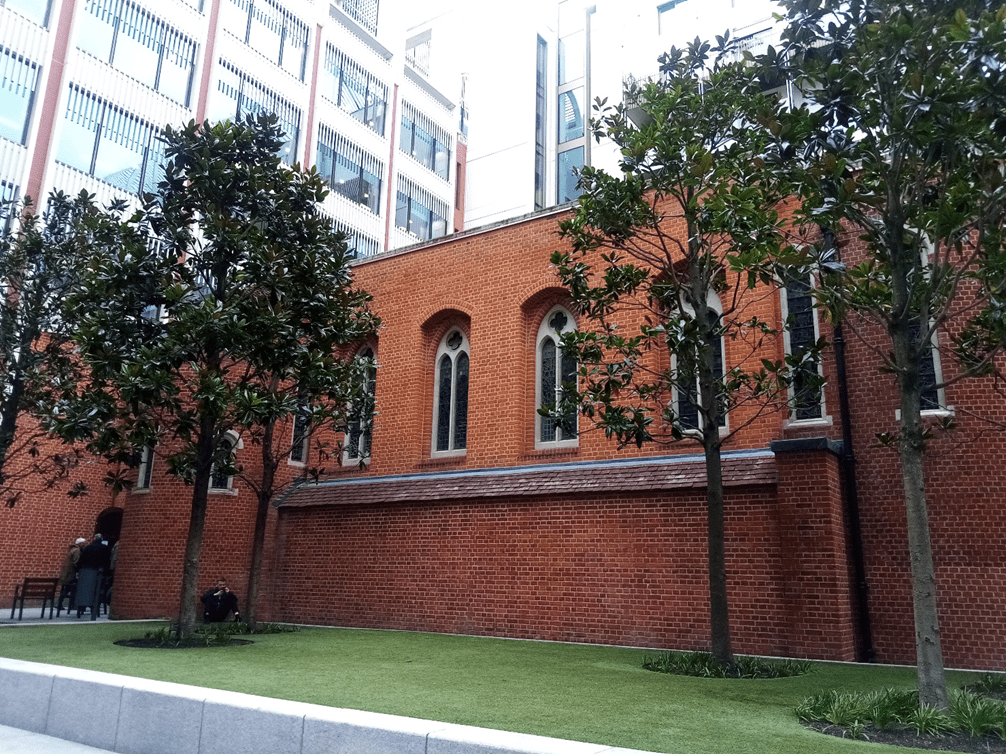

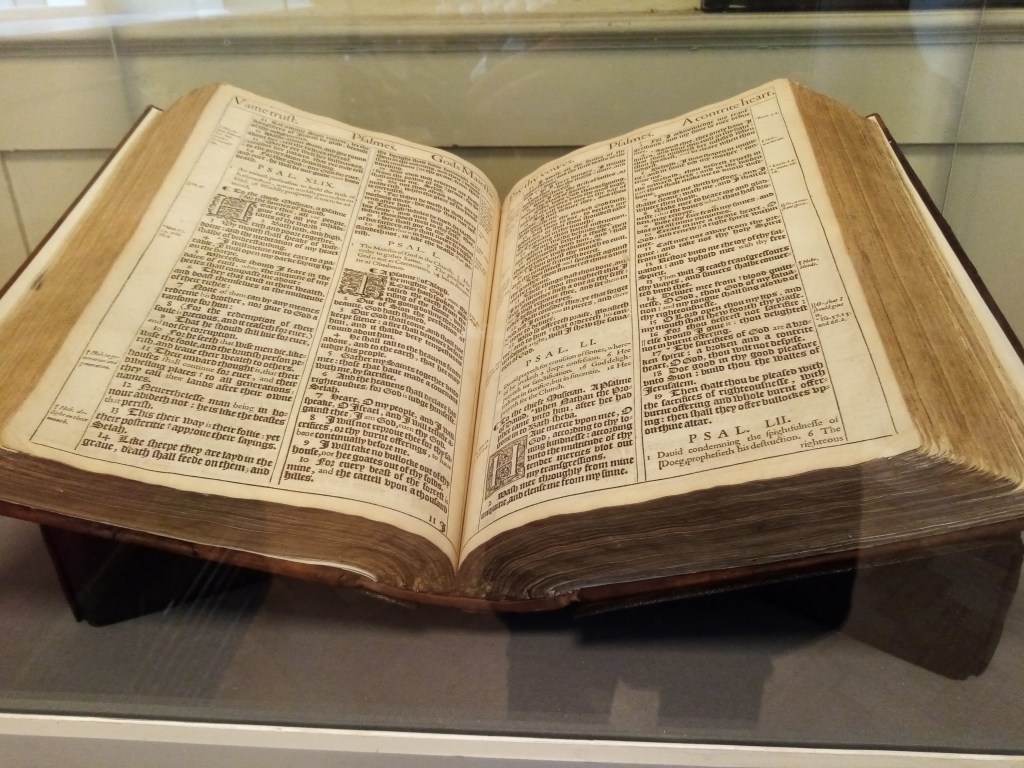

A Saxon church at ‘Maeldune’ was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, and incredibly, there are some remains of this church: an old flint and stone chancel wall were retained when the church was rebuilt in 1611. In 1596 the villagers of Malden petitioned Queen Elizabeth l asking for help to repair the church which had fallen into decay and was actually in ruins – but no help was forthcoming. However, in 1609 another appeal was made which was successful and the rebuilding of St John’s was scheduled, comprising a new red brick nave and tower and a new roof. In 1742 all the windows of the church were shattered when a gunpowder mill on the nearby Hogsmill River exploded! I liked the pretty memorial garden in the churchyard, and I discovered that the annual ‘Maeldune Fair’ was to be held on Saturday 22nd June on Plough Green with a special service to be held in the church on the Sunday – a quintessentially English summer’s day!

Source: stjohnsoldmalden.org.uk

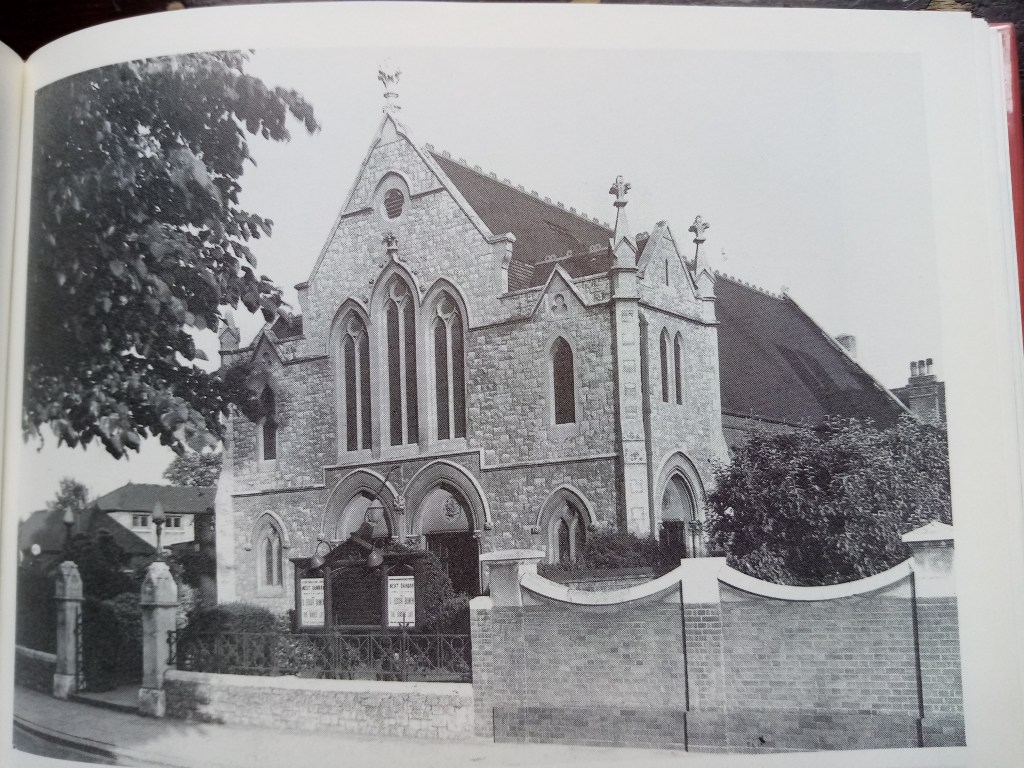

All Saints’ Church, Kenley

Much more recently built than the previous two churches, All Saints was completed in 1871. In the mid 19th century, the good folk of Kenley village would have had to travel several miles and across a valley to worship on a Sunday morning, to our first village church, St John’s in Old Coulsdon, which was their closest parish church. On horseback or by carriage, this journey would have taken about an hour. As the population inevitably increased, plans were made to build a church for Kenley Village. Four prominent local residents each contributed £535 towards the construction of the building and one of them donated the plot of land on Kenley Hill Field. The foundation stone was laid in November 1870 and the church was opened a year later. The designs were for a church congregation of 200; it was extended in 1901 to double seating capacity to 400. The extensions are in a different style to the original design of the building, which can be clearly seen as you wander round the building.

Source: allsaintsandstbarnabas.co.uk

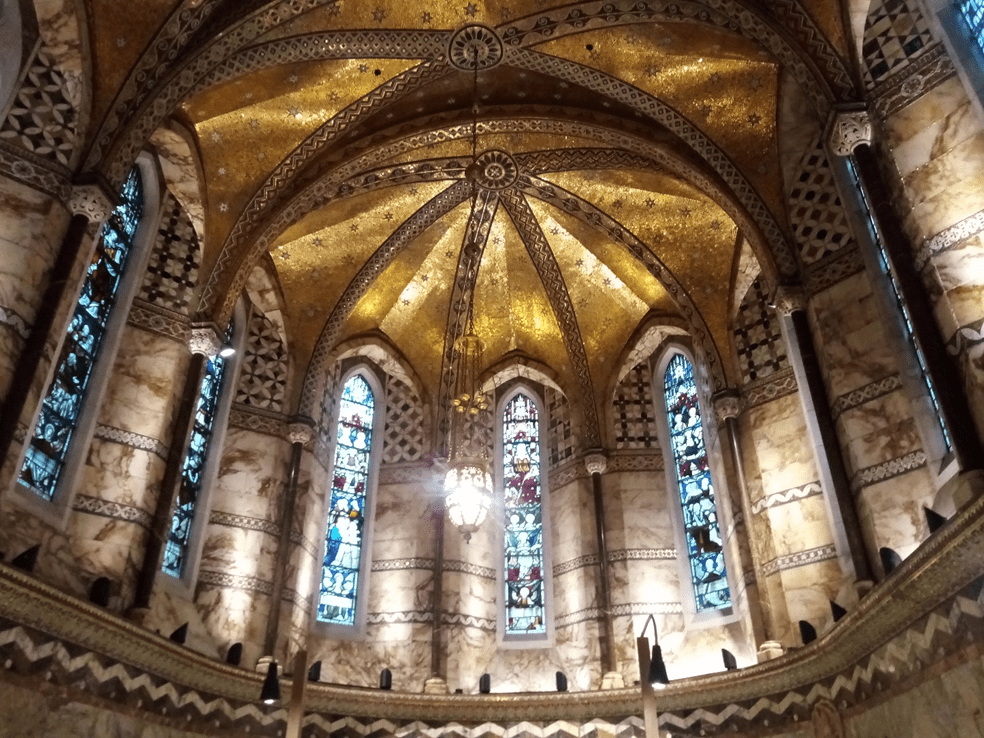

Round chancel of original building

Church tower

St Mary the Virgin, Addington Village

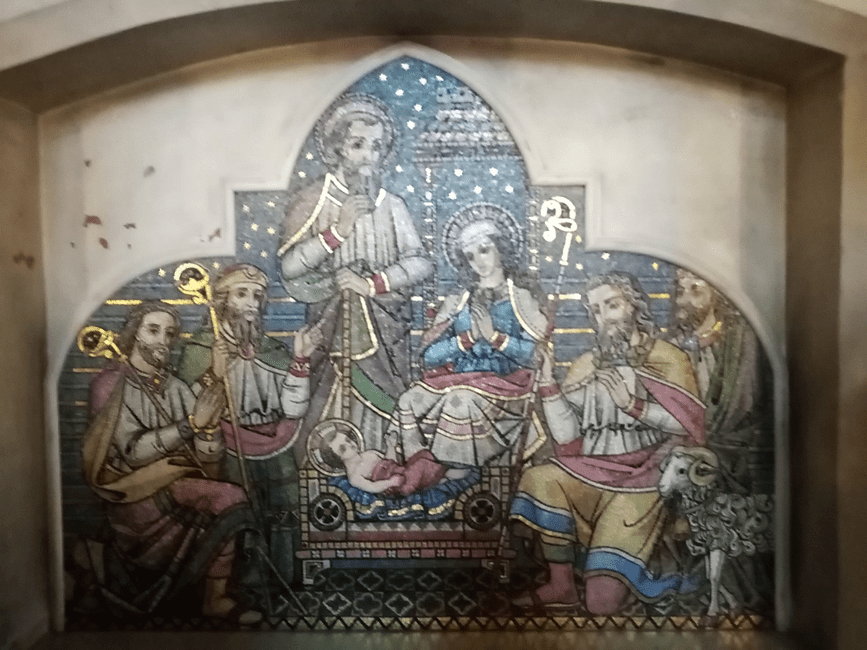

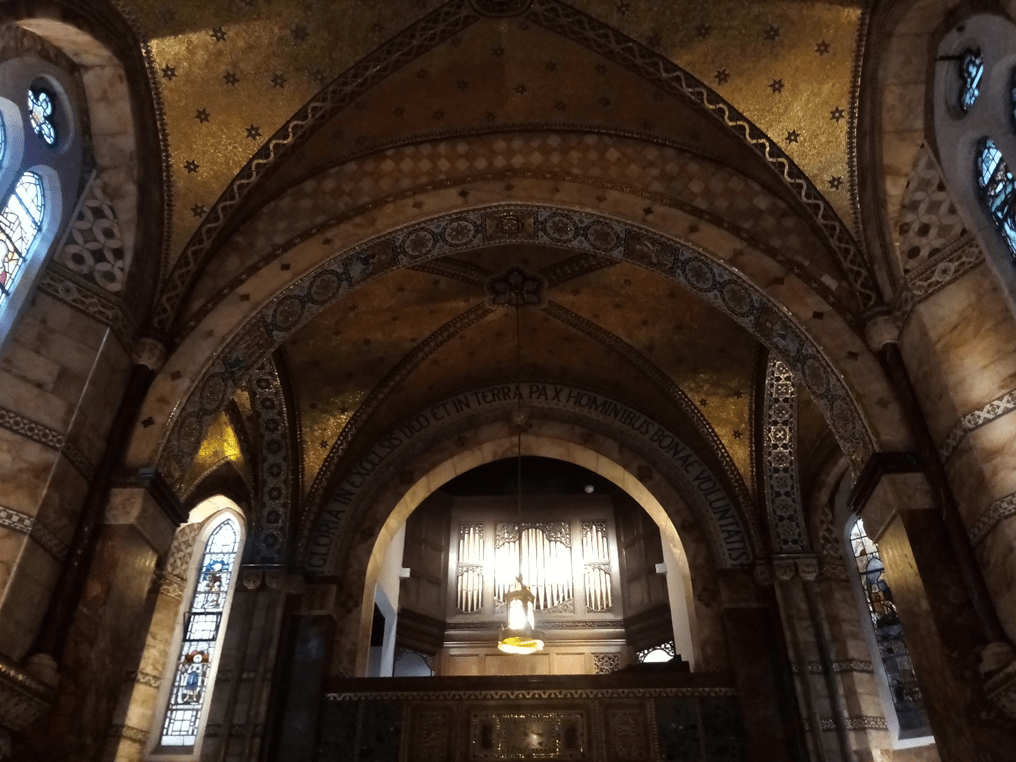

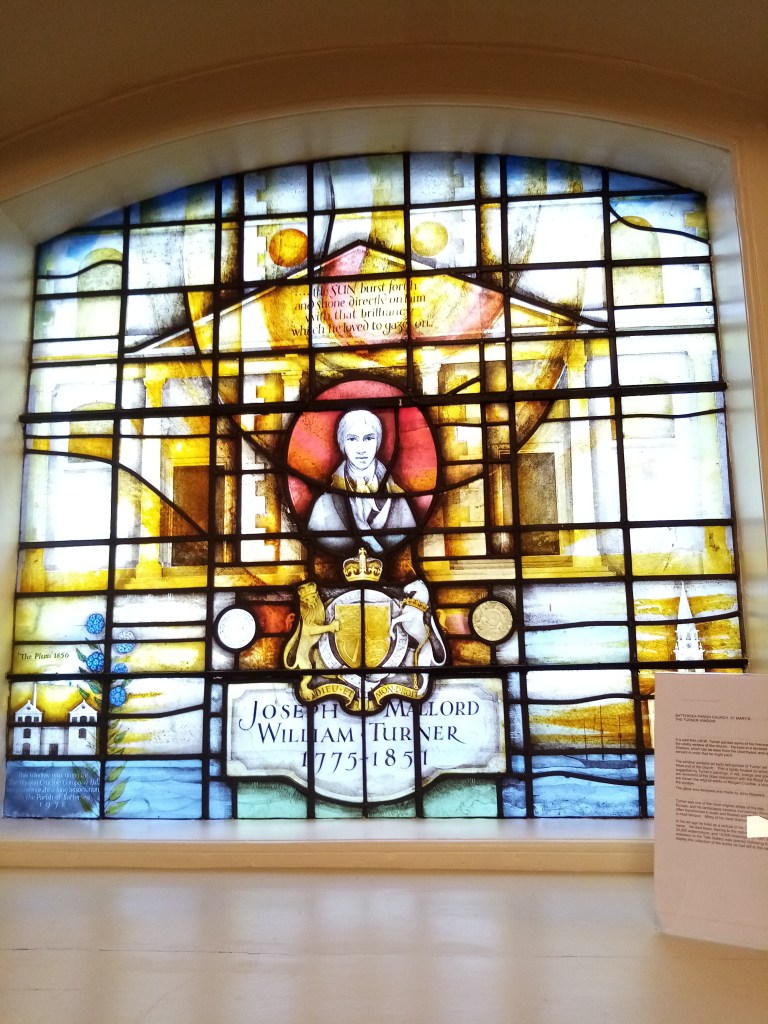

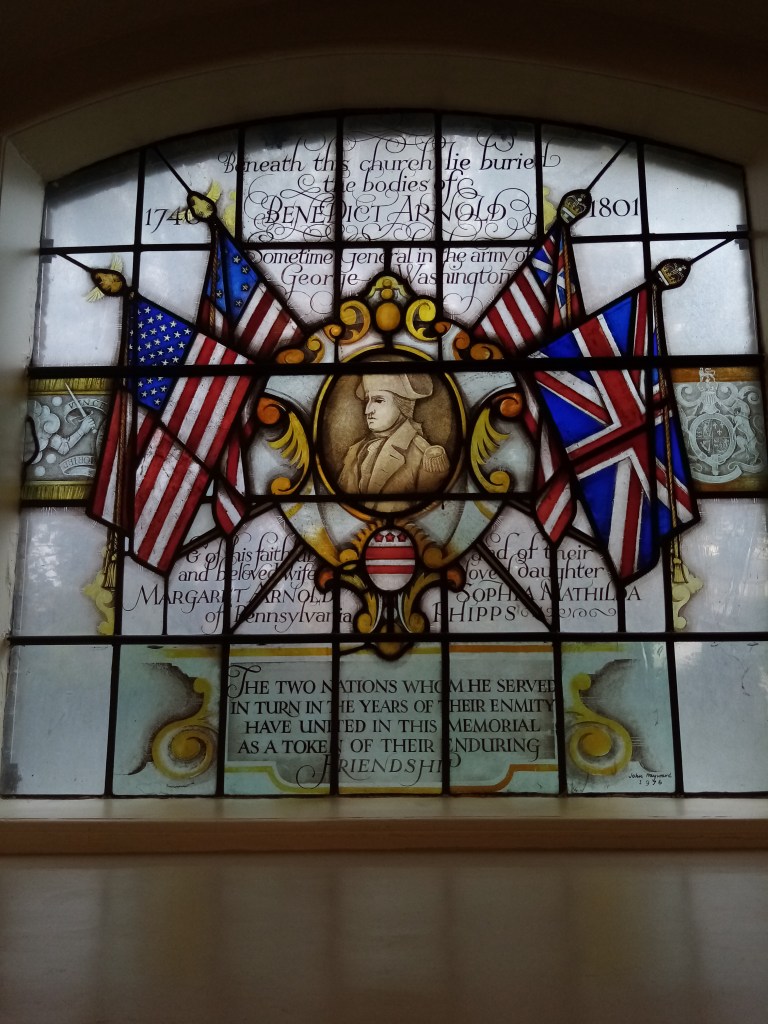

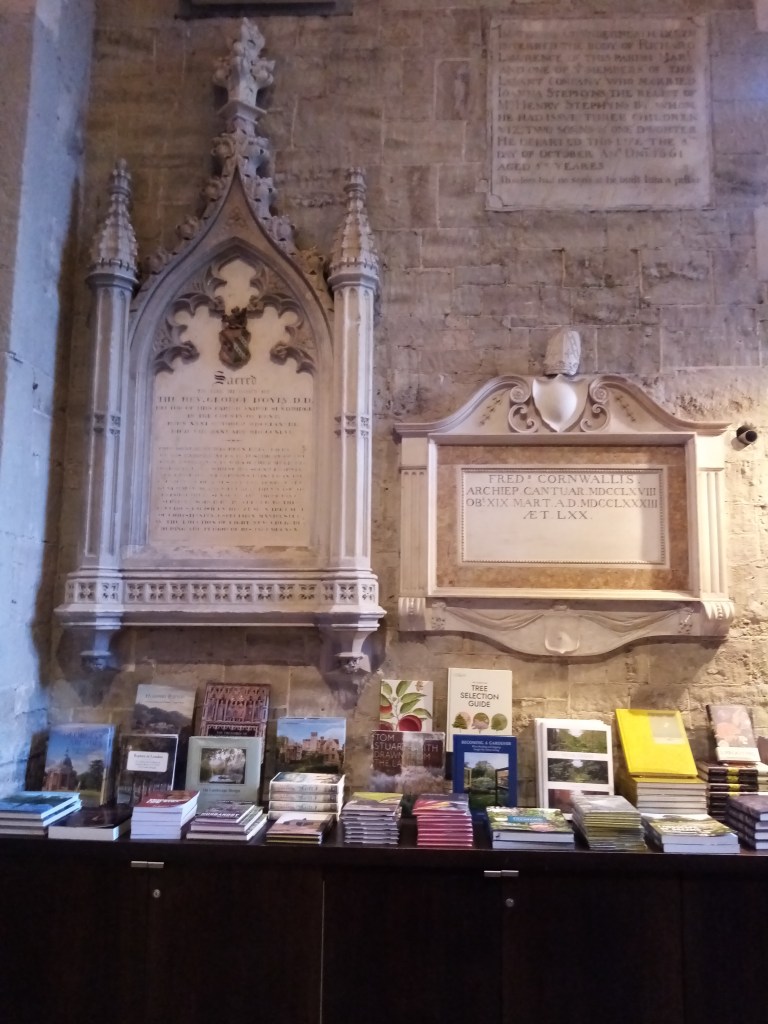

St Mary’s Addington was the place of worship for six Archbishops of Canterbury of the 19th century, whose summer residence was nearby Addington Palace. There is evidence for a church on this site since 1080 and the church is the oldest public building still in use in the Borough of Croydon. The chancel (altar area) and windows are 11th century and the south aisle, built in the 13th century, originally had a thatched roof, very unusual for a church. The church is open on weekdays so I had a chance to go inside and see the richly-decorated chancel, which looks quite spectacular in a small village church. These decorations aren’t original, they were painted in 1898 in memory of Archbishop Edward White Benson, the last of the six Archbishops to worship at St Mary’s; the other five Archbishops are buried in the crypt or churchyard. In the church are memorials to the Leigh family who were lords of the Manor of Addington for 300 years from the 15th century, and distantly related to the Carews of Beddington.

Sources: Wikipedia; addington.org.uk

Entrance to the church

Church tower

16th century headstone with skull and crossbones!