I featured some gardens in City churchyards in January 2021 when it wasn’t possible to go inside churches because of COVID restrictions. But I didn’t know that these small oases dotted around the City are known as Pocket Parks. Mostly frequented by office workers in their lunchbreaks, they are lovely, leafy green spaces to sit and relax, especially in Summer. Here are four from the west of the City of London; three are sites where the church is long gone, the fourth is a somewhat larger pocket next to a church, and one of my favourite parks. I’m hoping to look at another four over to the East next month.

Christchurch Greyfriars Churchyard

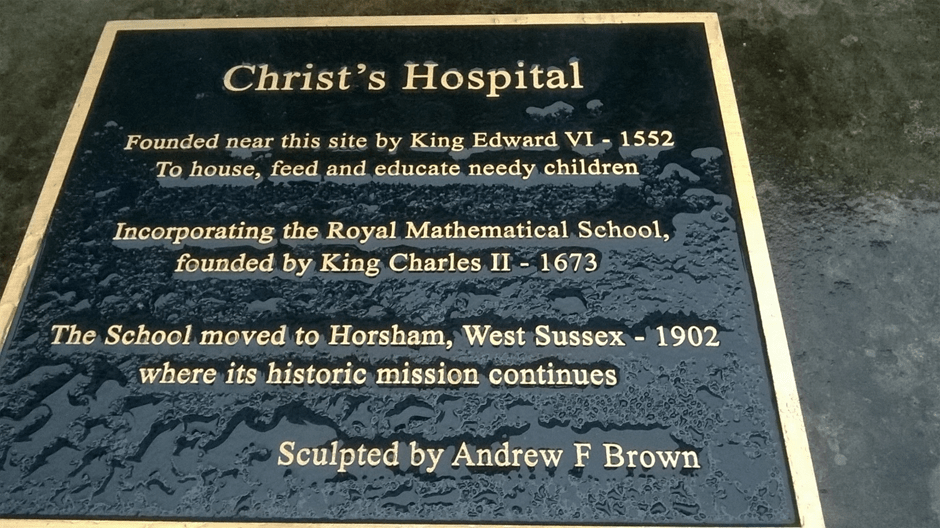

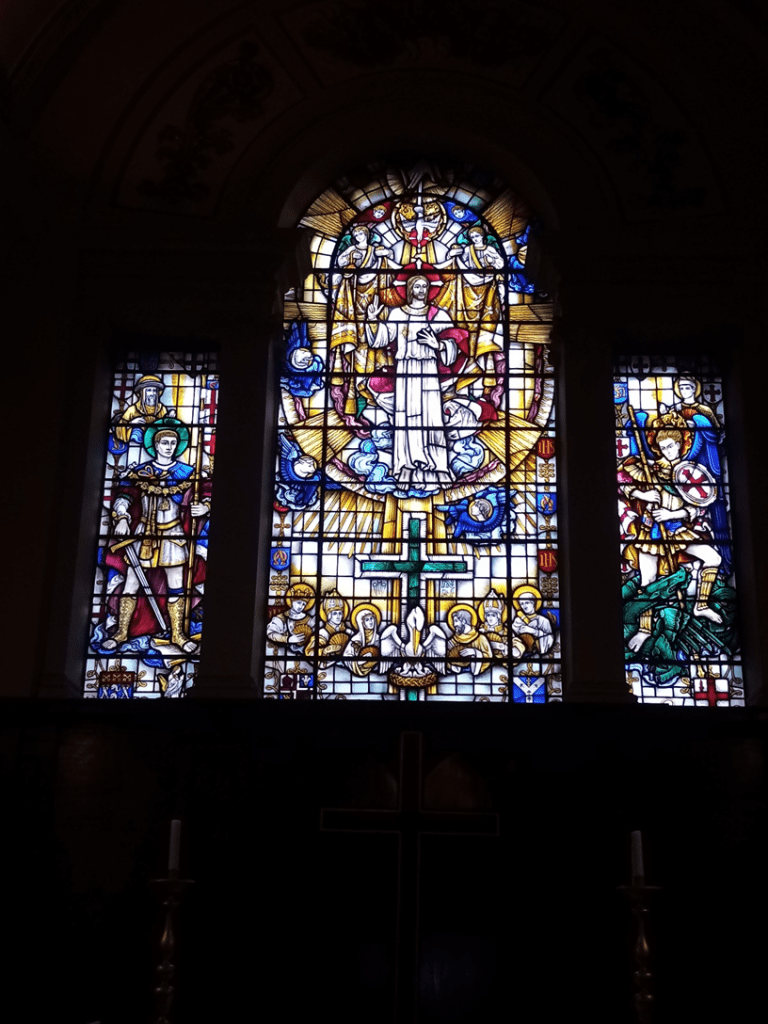

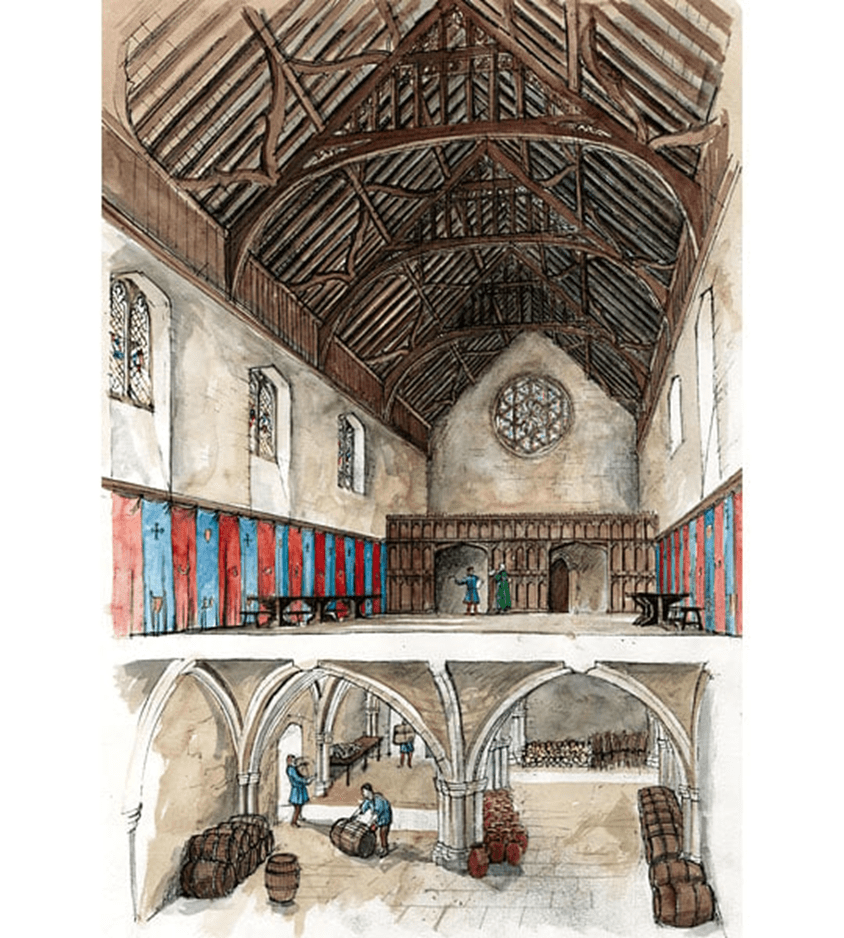

The garden is in two parts: a beautifully restored flower garden in the nave of the bombed-out Wren church (I wrote about this in ‘Romantic Ruins’ way back in February 2020), and this plain grassed area with shady trees and benches. The two areas are separated by the restored church tower which looks very dramatic from either side. The reason for including this very ordinary looking garden is because part of this site was once a huge Franciscan monastery. The name Greyfriars is a reference to the grey habits that the monks wore. The first building (1225) was quite small but the replacement, begun in the 1290s was much larger, the second largest religious building in Medieval London. It was 91m long and 27m wide and had 11 altars! These two plaques are on the wall of the Bank of America building adjacent to the park; it’s a huge building but the priory would have been bigger! The monastery was dissolved in 1538 in the Reformation and the building and fittings were badly damaged and looted, and left in ruins. But in 1546 Henry VIII gave the priory to the City Corporation and the buildings were converted into Christ’s Hospital School in 1552, founded by Henry’s son, Edward VI. The word hospital was also a term for place of education or shelter, not just a place for health care. The school remained on this site for the next 350 years, relocating to Horsham in 1902.

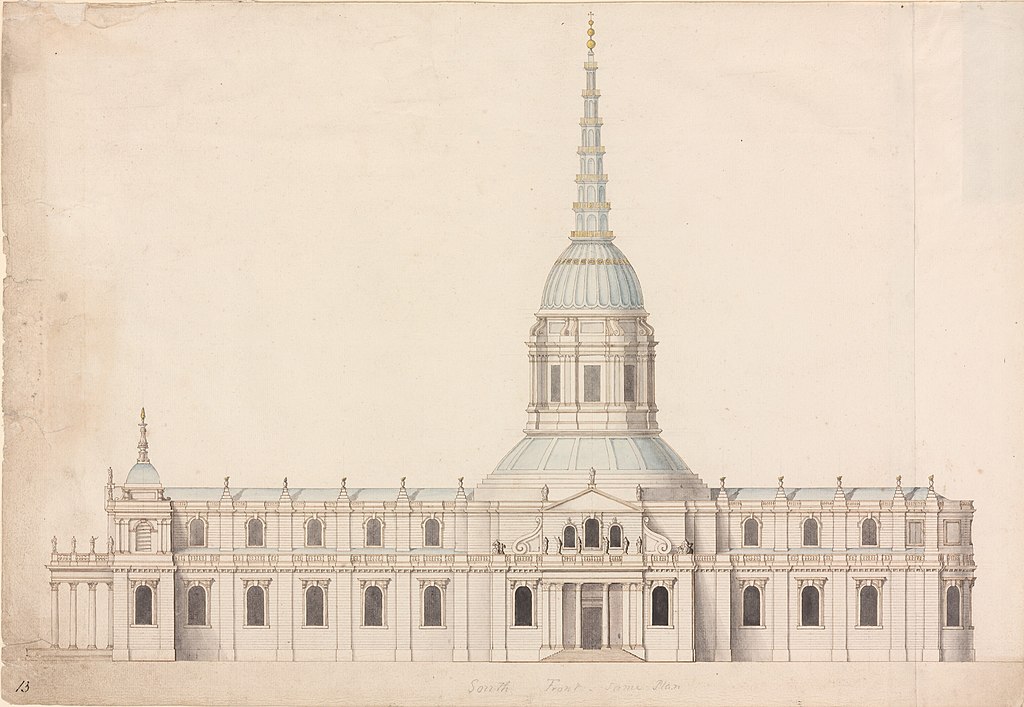

Source: Wikipedia

Goldsmith’s Garden

The next Pocket Park is Goldsmith’s Garden, former churchyard of St John Zachary. The original church, dedicated to John the Baptist (John, son of Zachary) was destroyed in the Great Fire and not rebuilt. The site was first laid out as a garden by World War Two fire wardens in 1941 and is now owned by the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths whose livery hall is across the road on the other side of Gresham Street. In 1995 the garden was refurbished by the Worship Companies named on the plaque above, creating the garden we see today. The garden is on two levels: at street level there are benches and flower borders with a huge London plane tree in the centre offering welcome shade. Down some steps to a square sunken garden with a small fountain in the middle of a grass lawn and in one corner, The Three Printers, a statue by Wilfred Dudeney. It depicts a newsboy, a printer and an editor, and surprisingly, is Britain’s only public monument to the newspaper industry. The statue was originally situated in New Street Square, Holborn but was relocated when the square was redeveloped. The other interesting items in the garden are these plaques of golden leopards, the symbol of the Goldsmiths’ Company.

Sources: Wikipedia; ianvisits.co.uk

Upper garden

Newspaper memorial

St Olave’s, Silver Street

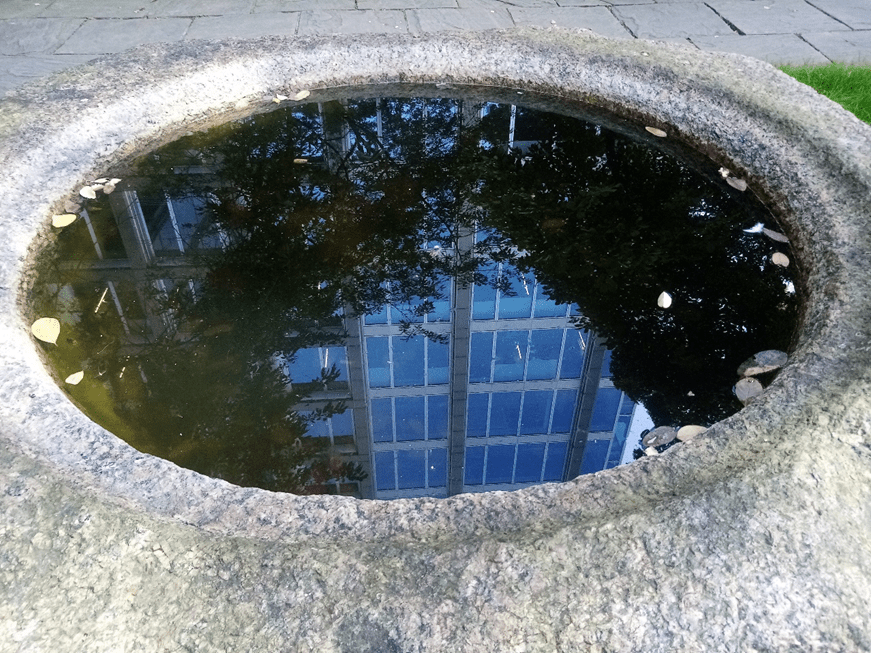

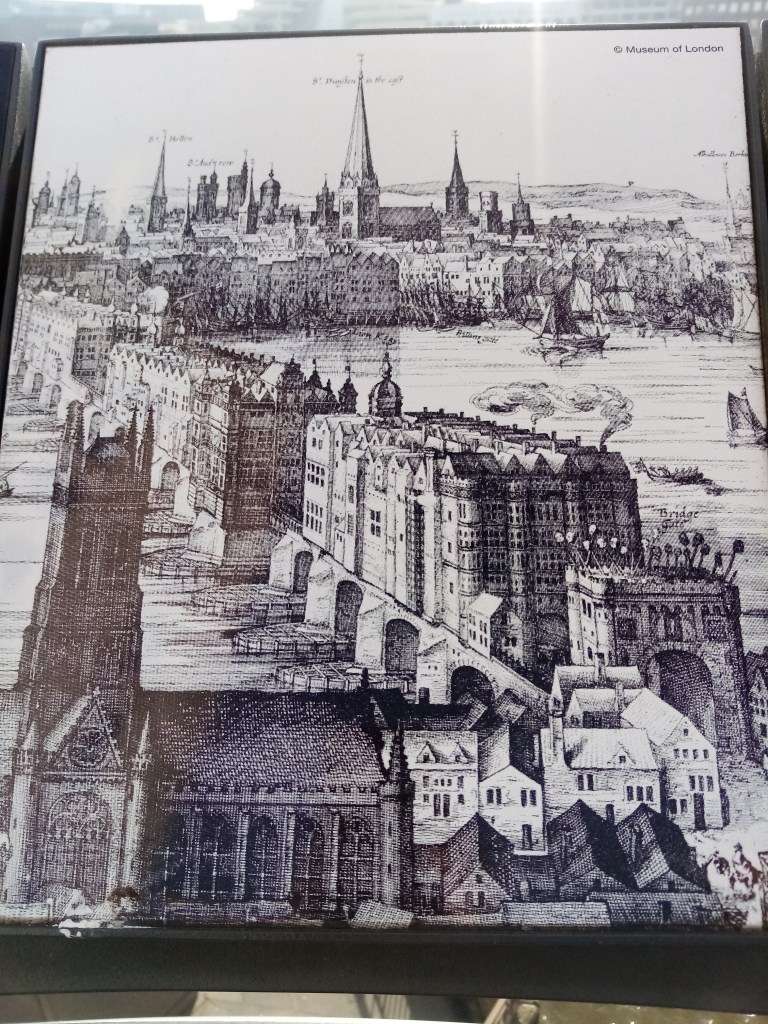

Photo taken from the garden looking towards 1 London Wall and the Museum of London

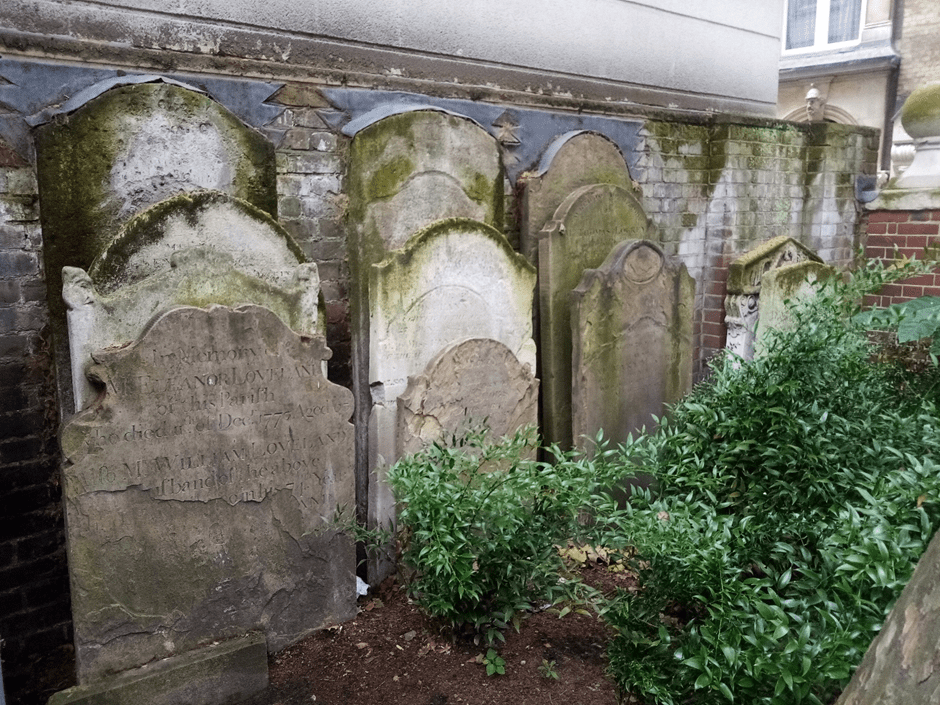

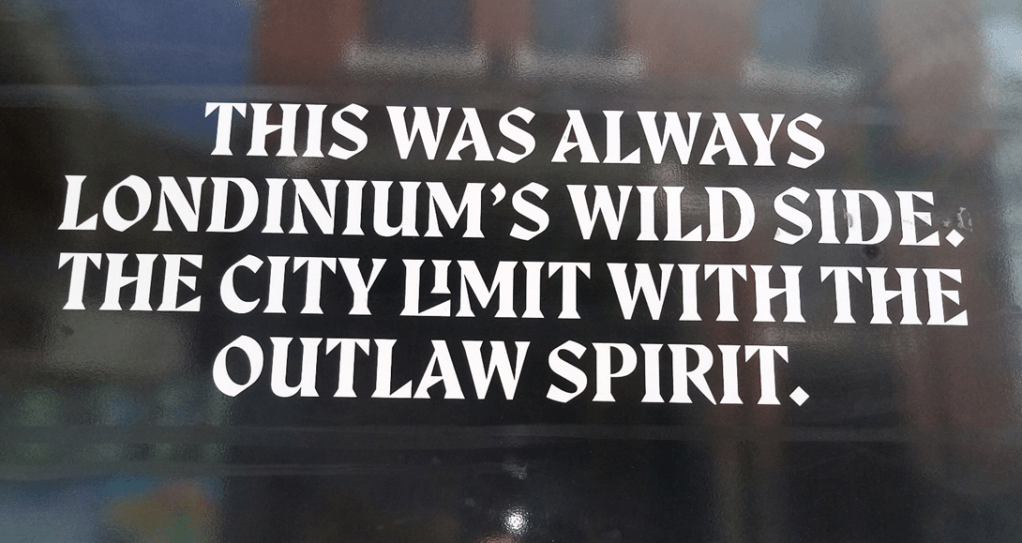

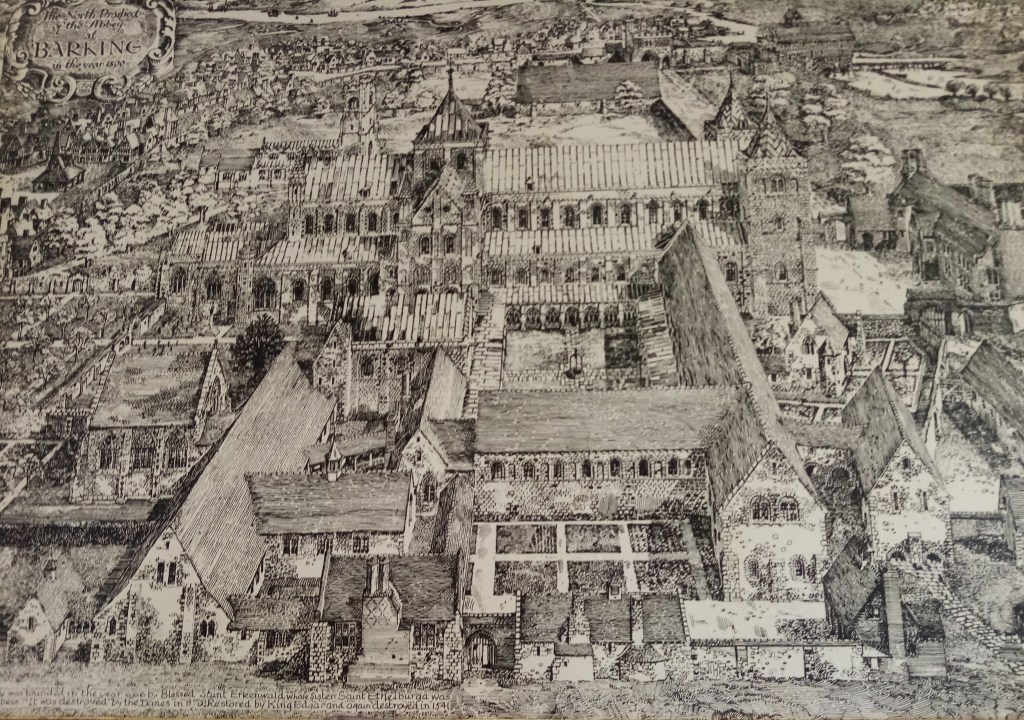

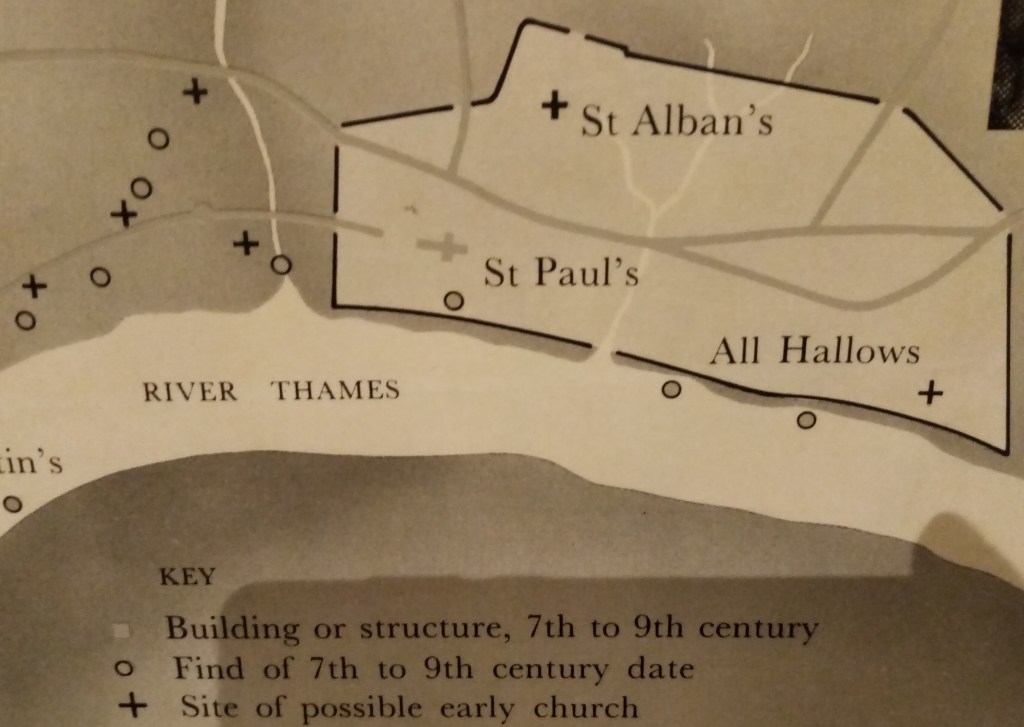

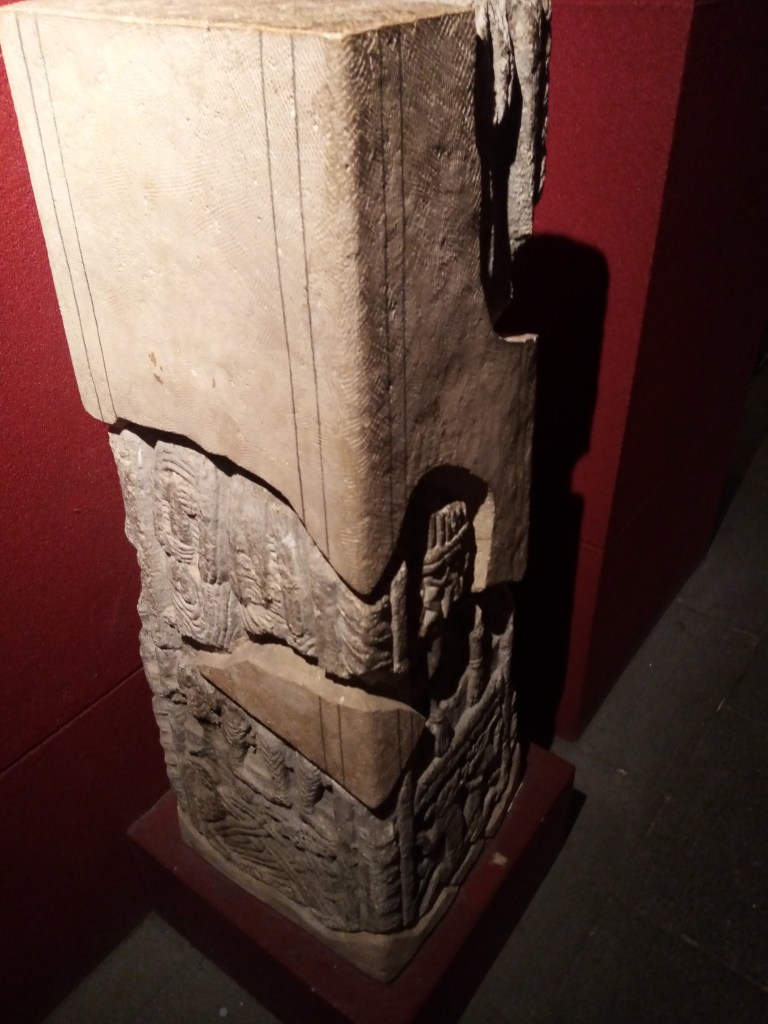

The Medieval London City landscape looked vastly different to how we see it today. Instead of modern office blocks of various sizes there were churches – lots of churches, so many of which did not survive fire and war. St Olave’s Silver Street is a stone’s throw from Goldsmith’s Garden and is on the corner of Noble Street and the dual carriageway that is London Wall. The church that stood here was destroyed in the Great Fire and never rebuilt but the site was maintained as a churchyard for burials. The church was dedicated to St Olaf, one of three churches with this name in the City; Olave is the anglicised spelling of Olaf. He was the first Christian king of Norway and fought alongside the English against the Vikings at the Battle of London Bridge in 1014. On his death, Olaf was canonised and remains the patron saint of Norway. This area was one of the most heavily bombed in World War Two, consequently it was completely redeveloped post-war, with the creation of the Barbican Estate and the construction of London Wall, which the original Silver Street became part of. Some interesting things about this Pocket Park: William Shakespeare lived on Silver Street for a few years in the early 1600s, very probably he attended St Olave’s. A very worn plaque, found in the rubble of the Blitz reads: ‘THIS WAS THE PARISH CHURCH OF ST OLAVE SILVER STREET DESTROYED BY THE DREADFULL FIRE IN THE YEAR 1666.’ And lastly, I love this reflective pool of water in what is probably one of the church’s columns.

Source: livinglondonhistory.com

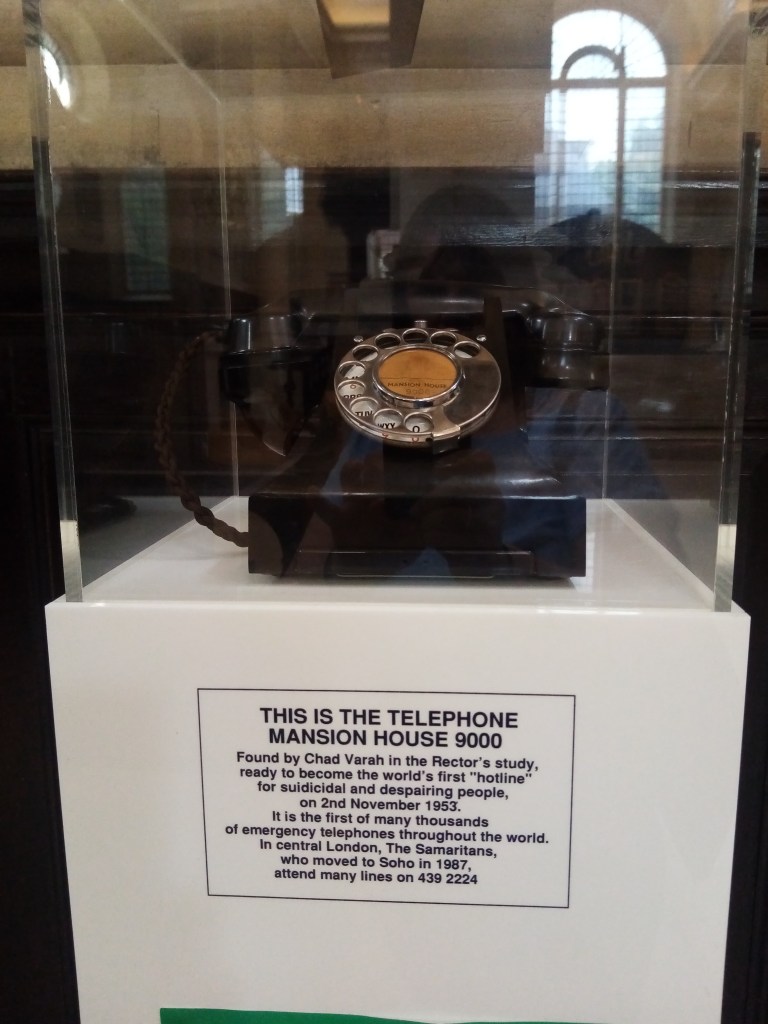

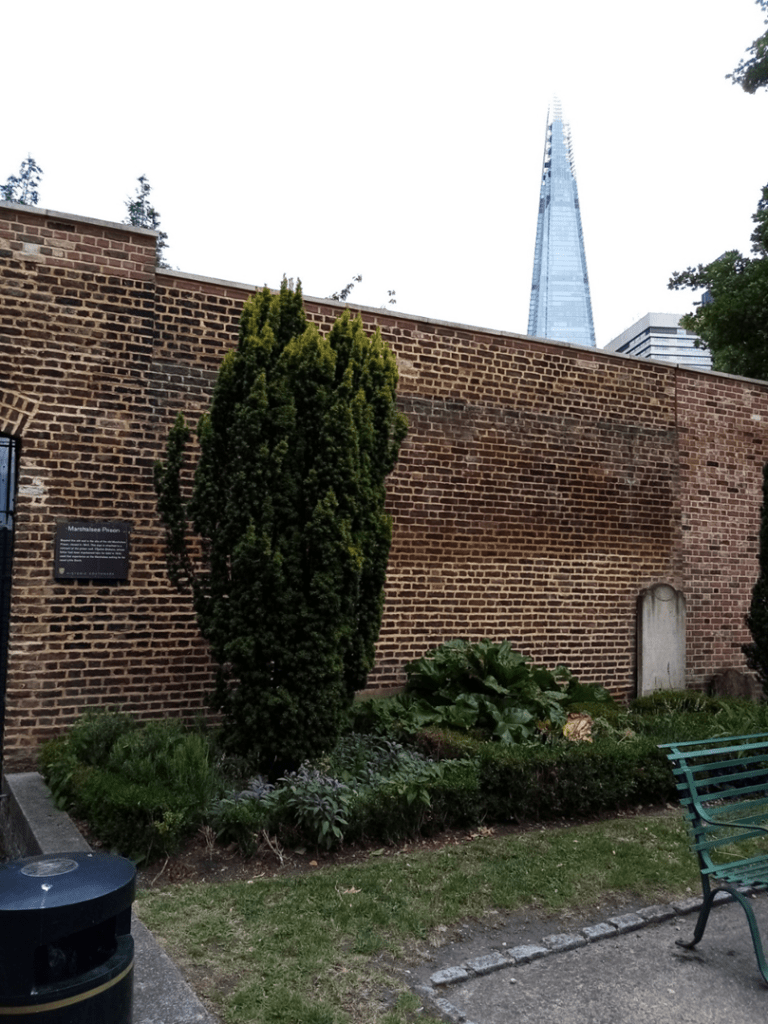

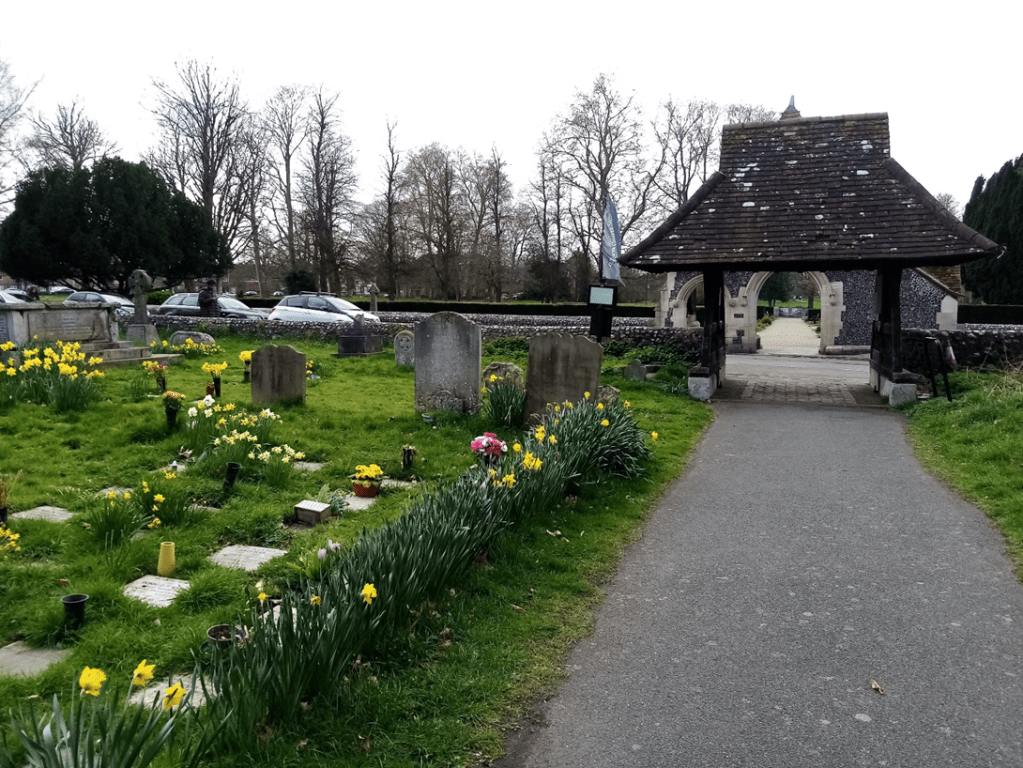

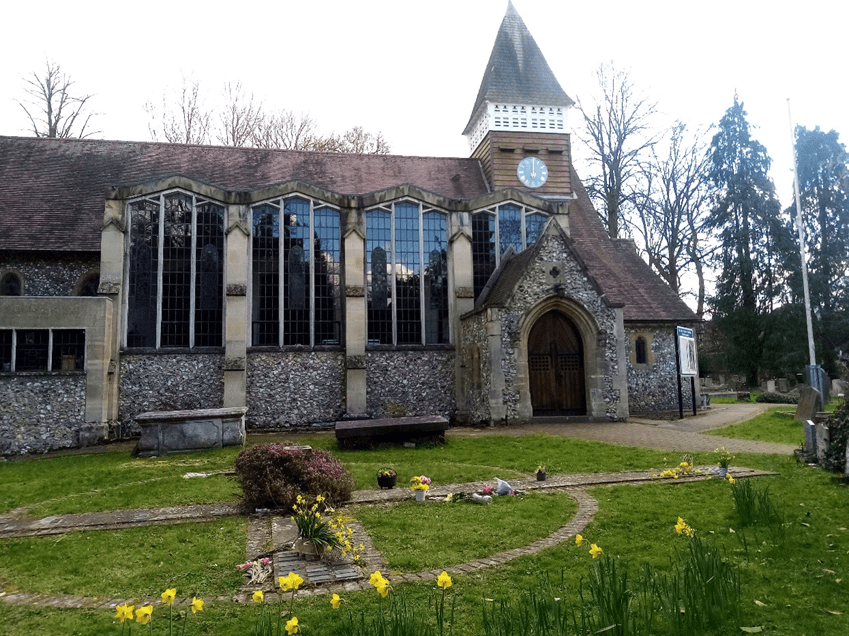

Postman’s Park

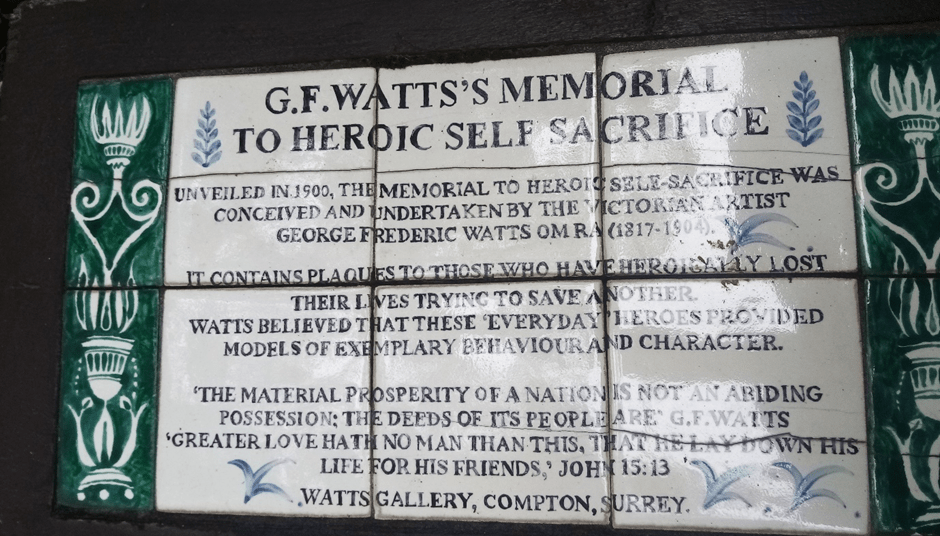

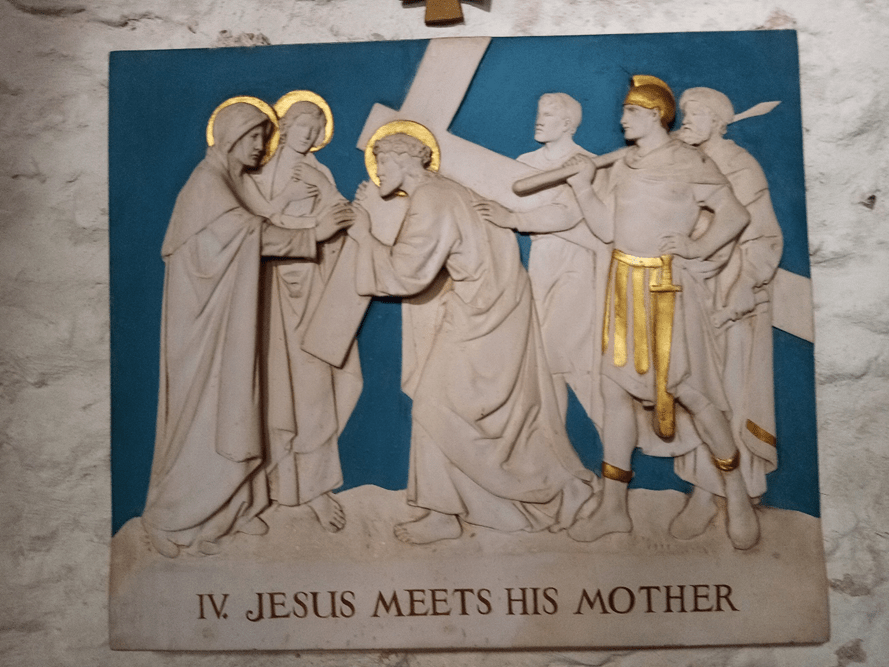

Postman’s Park opened in 1880 on the site of the former churchyard of St Botolph’s Aldersgate, a church still standing and in use (I wrote about it in ‘Churches on the London Wall’ February 2022). The Park is so named because the General Post Office (GPO) had its headquarters nearby and the park became very popular with workers in the building. The churchyard continued as a burial ground for the next 20 years and then in 1900, the artist and sculptor George Frederic Watts proposed a national monument be erected to the bravery and self-sacrifice of ordinary people. After rejecting the idea of a single huge bronze figure ‘a statue to Unknown Worth’, he came up with the idea of recording acts of self-sacrifice on individual tablets to be displayed on a memorial wall. The Vicar of St Botolph’s purchased the land from the City Parochial Foundation (who planned to build on it) and Watts himself paid the £700 (£84,000 in 2023) and Watt’s Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice was created. By the time of Watt’s death in 1904 only 13 of the planned 120 memorial tablets were in place; his wife Mary continued the project, overseeing the installation of a further 40. In 2009, a new tablet was added to the memorial, the first for 78 years. I love how spacious this park is and that it’s not overlooked by tall buildings, and has some lovely palms and ferns. Absolutely worth a visit, it’s where we stopped for lunch on my ‘Churches on the London Wall’ Walking Tour.

Source: Wikipedia

Ferns and…..

Palms in Postman’s Park!

And lastly….I spotted the City gardeners’ van, thanks guys!